William Friedkin

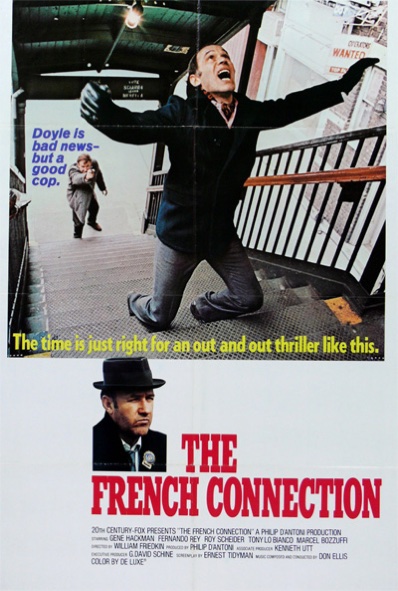

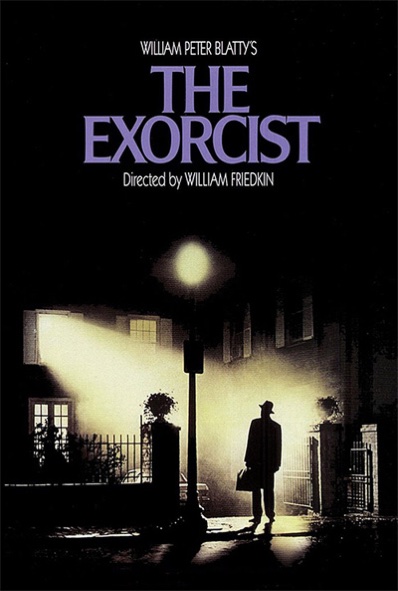

Best known for directing The French Connection in 1971 and The Exorcist in 1973; for the former, he won a Best Director Oscar. The latter is widely considered to be the best horror film ever made.

So much of what passes for “realism” today — unsteadicams working hard to hit their marks, washed-out colors, washed-up uglies stringing together drugged rants of inane profanities, weird lighting, piped-up ambient sounds, and the rare ambiguous ending — comes off as a meager, uneducated attempt at recapturing the ethos of the ’70s, and in particular, the realism of William Friedkin.

The director of “The Exorcist“, the world’s best horror film, a realist? Well, yes. Precisely. Compare it to the kingpin of bloody, overbearing, big and dumb, Brian DePalma, and you’ll feel the way smooth, natural action, suspense, and horror comes at you so believably that, in 1973, they were fainting in the aisles, and suing Warner Bros. when their heads hit the floor or the seat in front of them.

Friedkin’s first successes with film were TV documentaries for a station in his hometown of Chicago. They were so good they won awards at film festivals. Next thing, Friedkin is directing TV episodes and getting chastised by Alfred Hitchcock for not wearing a tie as he’s directing the last episode of “Alfred Hitchcock Presents”.

His first feature, “Good Times”, in 1967, starred Sonny and Cher. The next year, he made the film adaptation of Harold Pinter’s “The Birthday Party”, starring Robert Shaw and Patrick Magee, and the notable “The Night They Raided Minsky’s”. Pretty clean for a 1968 film about burlesque and vaudeville, “Minsky’s” blended a fast-paced backstage realism with an extremely fast-paced, completely self-referential, and unrealistic ’60s style editorial montage. It is a burlesque itself — clever, over the top, funny, and more talk than sex — a regular ’20s ballyhoo. Still doing the art thing, Friedkin acquired a lot of admirers with his adaptation of Off-Broadway’s gay play, “The Boys in the Band”, with the original stage cast. (He would lose them eventually with “Cruising”.)

Then Fox President Richard Zanuck gave Friedkin just enough money to be creative with a true story, “The French Connection“. Friedkin went back to the medium that he loved most, documentary, for his now-famous style. No storyboards. Friedkin still believes they tie the film down and inhibit those special moments that happen by chance. And he couldn’t afford stars, so he took Gene Hackman and Roy Scheider and made them stars. They deserved it, too. They all rode around with the real cops that Russo and Popeye Doyle are based upon (who also have roles in the movie), and picked up that NYPD sound and fury, and then went out and did it themselves, making up much of the dialogue and most of the bits as they went along.

And the camera work? (This is a secret, revealed on the DVDs, which all the aforementioned contemporary imitators would do well to heed.) Friedkin never told his camera people what the action would be. They were left to find it themselves. But still struggling to be “professionals”, the cameramen would make their jerks and searches as subtle as possible, leaving the audience with the feeling that not only are they in the action but everything is moving so quickly they are struggling to keep up.

Friedkin admits to putting people in harm’s way (though not the lady with the carriage; that’s an editing trick) in the famous el-train chase, and vows that he would never do that again. [Though some still prefer the “Bullitt” chase, it certainly doesn’t compare in the realm of realism.] Referring to directing as a young man’s game for that very reason, Friedkin admits that he was young, daring and ambitious, and that the film came first. The crashes in the sequence are all literally accidents, the fault of poor stunt drivers missing their cues, Friedkin says. He didn’t have the money to shut down the road, so he put Gene in the car and Gene floored it. And that was that. It is now referred to as “induced documentary” style.

Part of that inducement, apparently, is the slapping of a real priest, Father William O’Malley, on the set of “The Exorcist”, to get him to show the right emotion. No telling what kind of damage Linda Blair suffered; she did have to have a bodyguard for months after the film’s opening because of all the death threats. Ellen Burstyn, though, suffered permanent damage to her spine in a scene where she is “thrown” back by the force of her daughter. Those screams of agony as she lands are not, this time, acting.

In the category of awards, “The French Connection” cleaned house, taking home five Oscars, including Best Picture and a Best Director for Friedkin, as well as many other awards. Though “The Exorcist” is truly one of the best crafted films there is, it had to settle for winning a Golden Globe and being nominated for ten Oscars.

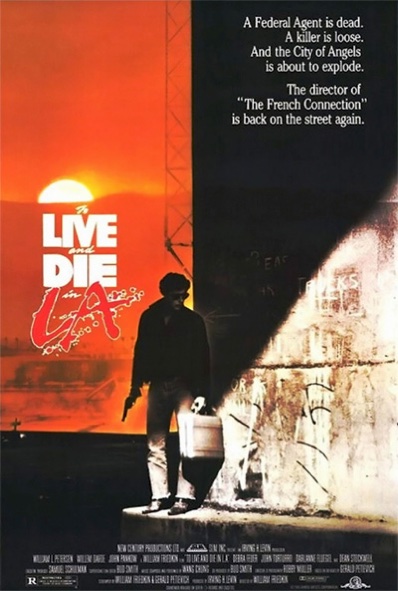

It was not until 1985, when Friedkin returned to a favorite theme — the conflict of good and evil within all of us — that he scored. This time it was “To Live and Die in L.A”., still remembered as the West Coast version of “The French Connection”, which isn’t a bad comparison. Before, it was a pizza-noshing Hackman versus the gourmet Fernando Rey, and the haggard Max von Sydow versus the really haggard Linda Blair. Now, the “mano a mano” got closer and more personal with Billy Petersen versus Willem Dafoe.

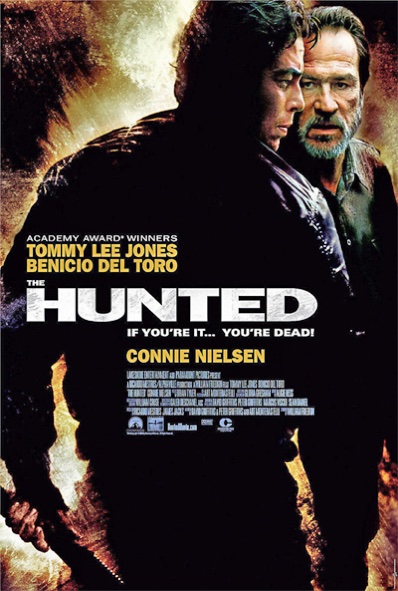

This ethos, along with the “induced documentary”, served Friedkin brilliantly in a Showtime remake of “12 Angry Men“, with a huge cast of stars headed by Jack Lemmon. Then, again, as he says it, he just turned on the camera and watched while Guy Pierce took on Tommy Lee Jones and Samuel Jackson, mano a mano, in “Rules of Engagement”. The fascinating “Hunted”, again with startling realistic camera work, pitted Tommy Lee Jones as a tracker and trainer of killers against his best student, Benicio del Toro, who’s gone crazy, killing more than just bad guys.

Now in his seventies, William Friedkin is directing what is perhaps the most stylized medium of them all — opera. Working with Los Angeles Opera, among other companies, Friedkin has directed in Europe, Israel, and on both coasts. And, if he has his way, there will be a new term soon — documentary-induced opera.

— Nate Lee

Great Scenes

The French Connection

- The chase scene of Gene Hackman’s Popeye Doyle in a car chasing the French assassin who is on the elevated train is considered one of the four best chase scenes in cinema. Ripping the car apart looking for the drugs

- Hackman losing Fernando Rey on the subway. Friedkin’s commentary on the DVD is fascinating

The Exorcist

- Generally regarded as the best horror film ever, and third in suspense to Jaws and Psycho. Take your pick of the confrontation scenes between Max von Sydow and Blair Regan: the pea soup; floating; the head turning around… or the taunting of Jason Miller as Father Damien, the junior exorcist

- Yes, the film is riddled with subliminal cuts. The added scenes on the DVD are interesting mostly if you’ve seen the original first, just to compare and appreciate the utter tautness of the original

To Live and Die in L.A.

- Willem Dafoe is mesmerizing as the villain, who regards his counterfeiting as works of art

Rules of Engagement

- The final summation scenes in which Guy Pierce as the prosecutor and Tommy Lee Jones square off are exquisite in their lack of cutting and realistic flavor. Samuel Jackson is more effective in the scenes where he sits in silent disbelief than in his characteristic staccato tirades

The Night They Raided Minsky’s

- Though much of the film has the quasi-documentary feel of Friedkin’s other work, it is the fascinating editorial montage sequences that make this film about ’20s burlesque so interesting

The Hunted

- The knife fights between Benicio Del Toro and Tommy Lee Jones are superior to slow-motion martial arts shots because they are so realistic and deadly fast. Jones’s tracking and rescuing a wolf in the beginning beautifully, silently and effectively portrays a fascinatingly complex character

Best Films

- The Exorcist

- French Connection

- To Live and Die in L.A.

- The Rules of Engagement

- The Hunted

- The Night They Raided Minsky’s

William Friedkin’s directing credits include…

| Year | Movie |

|---|---|

| 1967 | Good Times |

| 1968 | The Birthday Party |

| 1968 | The Night They Raided Minsky’s |

| 1970 | The Boys in the Band |

| 1971 | The French Connection |

| 1973 | The Exorcist |

| 1977 | Sorcerer |

| 1978 | The Brink’s Job |

| 1980 | Cruising |

| 1983 | Deal of the Century |

| 1985 | To Live and Die in L.A. |

| 1985 | The Twilight Zone |

| 1986 | C.A.T. Squad (aka Stalking Danger) |

| 1987 | Rampage |

| 1988 | C.A.T. Squad: Python Wolf |

| 1990 | The Guardian |

| 1994 | Blue Chips |

| 1994 | Jailbreakers |

| 1995 | Jade |

| 1997 | 12 Angry Men |

| 2000 | Rules of Engagement |

| 2003 | The Hunted |

| 2006 | Bug |

| 2011 | Killer Joe |