W.S. Van Dyke

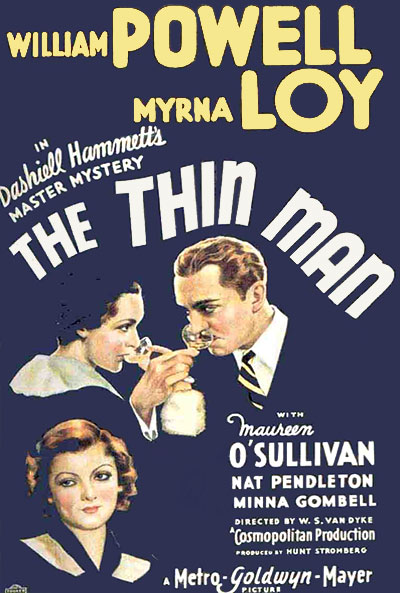

Best known for his successful directorial work in Hollywood’s early “talkies” era, including Tarzan the Ape Man in 1932, The Thin Man in 1934, San Francisco in 1936, and six popular musicals with Nelson Eddy and Jeanette MacDonald.

Woodbridge Strong Van Dyke II was born on March 21, 1889 in San Diego, California. His father was a Superior Court judge who died the day his son was born. His mother, Laura Winston, returned to her former acting career. As a child actor, Van Dyke appeared with his mother on the vaudeville circuit with traveling stock companies. They traveled up and down the coast and into the Middle West. When he was five years old, they appeared at the old San Francisco Grand Opera House in Blind Girl. He would later remember his unusual education, “I think I’ve been to school in every state in the Union. Whenever the company stopped off long enough in any city I went back behind a school desk. The rest of the time my mother taught me.”

When Van Dyke was fourteen years old, he moved to Seattle to live with his grandmother. While attending business school, he worked a number of part-time jobs, including janitor, waiter, salesman, and railroad attendant. Van Dyke’s early adult years were unsettled, and he moved from job to job. In 1909, he married actress Zelda Ashford, and the two joined various touring theater companies, finally arriving in Hollywood in 1915.

In 1915, Van Dyke found work as an assistant director to D. W. Griffith on the film The Birth of a Nation. The following year, he was Griffith’s assistant director on Intolerance. That same year he worked as an assistant director to James Young on Unprotected (1916), The Lash (1916), and the lost film Oliver Twist, in which he also played the role of Charles Dickens.

In 1917, Van Dyke directed his first film, The Land of Long Shadows for Essanay Studios. That same year he directed five other films: The Range Boss, Open Places, Men of the Desert, Gift O’ Gab, and Sadie Goes to Heaven. In 1927, he traveled to Tacoma to direct two silent films for the new H.C. Weaver Productions: Eyes of the Totem and The Heart of the Yukon (the latter is considered a lost film).

During the silent era he learned his craft and with the introduction of talkies was one of MGM’s most reliable directors. He came to be known as “One-Take Woody” or “One-Take Van Dyke”, for the speed with which he would complete his assignments, and although not regarded as one of the screen’s most gifted directors, MGM regarded him as one of the most versatile, equally at home with costume dramas, westerns, comedies, crime melodramas, and musicals.

Many of his films were huge hits and top box office in any given year. He received Academy Award nominations for Best Director for The Thin Man (1934) and San Francisco (1936). He also directed the Oscar-winning classic Eskimo (also known as Mala the Magnificent), in which he also has a featured acting role.

His other films include the island adventure White Shadows in the South Seas (1928), its follow up The Pagan (1929), Trader Horn (1931) filmed almost entirely in Africa, Tarzan the Ape Man (1932), Manhattan Melodrama (1934), and Marie Antoinette (1938). He is perhaps best remembered for directing Myrna Loy and William Powell in four Thin Man films: The Thin Man (1934), After the Thin Man (1936), Another Thin Man (1939), and Shadow of the Thin Man (1941); and Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy in six of their greatest hits, Naughty Marietta (1935), Rose Marie (1936), Sweethearts (1938), New Moon (1940) (uncredited because halfway through filming Robert Z. Leonard took over), Bitter Sweet (1940), and I Married an Angel (1942).

The earthquake sequence in San Francisco is considered one of the best special-effects sequences ever filmed. To help direct, Van Dyke called upon his early mentor, D. W. Griffith, who had fallen on hard times. Van Dyke was also known to hire old-time, out-of-work actors as extras. Because of his loyalty, he was much beloved and admired in the industry.

Van Dyke was known for allowing ad-libbing (that remained in the film) and for coaxing natural performances from his actors. He made stars of Nelson Eddy, James Stewart, Myrna Loy, Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O’Sullivan, Eleanor Powell, Ilona Massey, and Margaret O’Brien. He was often called in to work a few days (or more), uncredited, on a film that was in trouble or had gone over production schedule.

Promoted to Major prior to World War II, the patriotic Van Dyke set up a Marine Corps recruiting center in his MGM office. He was one of the first Hollywood bigwigs to advocate early U.S. involvement, and he convinced stars like Clark Gable, James Stewart, Robert Taylor, and Nelson Eddy to become involved in the war effort.

Ill with cancer and a bad heart, he directed one last film: Journey for Margaret. It was a heart-rending movie that made five-year-old Margaret O’Brien an overnight star.

A devout Christian Scientist, Van Dyke refused most medical care during his last years. After finishing his last film, he said his goodbyes to his wife, children, and studio boss Louis B. Mayer and committed suicide on February 5, 1943 in Brentwood, Los Angeles. At his request, Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy both sang and officiated at his funeral.

W.S. Van Dyke’s directing credits include…

| Year | Movie |

|---|---|

| 1917 | The Land of Long Shadows |

| 1917 | The Range Boss |

| 1917 | Open Places |

| 1917 | Men of the Desert |

| 1917 | Gift O’ Gab |

| 1917 | Sadie Goes to Heaven |

| 1918 | The Lady of the Dug-Out |

| 1919 | The Hawk’s Trail |

| 1920 | Daredevil Jack |

| 1921 | Double Adventure |

| 1922 | Forget Me Not |

| 1921 | The Avenging Arrow |

| 1922 | White Eagle |

| 1924 | Half-A-Dollar-Bill |

| 1924 | Loving Lies |

| 1924 | Gold Heels |

| 1925 | The Trail Rider |

| 1926 | The Gentle Cyclone |

| 1926 | War Paint |

| 1927 | Winners of the Wilderness |

| 1927 | California |

| 1927 | Spoilers of the West |

| 1927 | Eyes of the Totem |

| 1928 | Under the Black Eagle |

| 1928 | Wyoming |

| 1928 | White Shadows in the South Seas |

| 1929 | The Pagan |

| 1931 | Trader Horn |

| 1931 | The Cuban Love Song |

| 1932 | Tarzan the Ape Man |

| 1932 | Night Court |

| 1933 | Penthouse |

| 1933 | The Prizefighter and the Lady |

| 1933 | Eskimo |

| 1934 | Manhattan Melodrama |

| 1934 | The Thin Man |

| 1934 | Hide-Out |

| 1934 | Forsaking All Others |

| 1935 | I Live My Life |

| 1936 | Rose Marie |

| 1936 | San Francisco |

| 1936 | His Brother’s Wife |

| 1936 | The Devil Is a Sissy |

| 1936 | Love on the Run |

| 1936 | After the Thin Man |

| 1937 | They Gave Him a Gun |

| 1937 | Personal Property |

| 1938 | Marie Antoinette |

| 1938 | Sweethearts |

| 1939 | Stand Up and Fight |

| 1939 | It’s a Wonderful World |

| 1939 | Andy Hardy Gets Spring Fever |

| 1939 | Another Thin Man |

| 1940 | I Take This Woman |

| 1940 | I Love You Again |

| 1940 | Bitter Sweet |

| 1941 | Rage in Heaven |

| 1941 | The Feminine Touch |

| 1941 | Shadow of the Thin Man |

| 1942 | Dr. Kildare’s Victory |

| 1942 | I Married an Angel |

| 1942 | Cairo |

| 1942 | Journey for Margaret |

Memorable Quotes by W.S. Van Dyke

[on ‘The Thin Man’] “We shot it in sixteen days, retakes and all. And that sweet smell of success was in every frame.”

Things You May Not Know About W.S. Van Dyke

Before entering the movie business, Van Dyke was a gold miner, a lumberjack, a railroad worker and a mercenary.

Directed four different actors in Oscar-nominated performances: William Powell, Spencer Tracy, Robert Morley and Norma Shearer.

He was close friends outside of the studio with Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy, and at his request they officiated at his funeral and sang.

Louis B. Mayer was deeply shaken by Van Dyke’s suicide. Van Dyke was one of his favorite directors (Mayer always admired a director capable of consistently bringing projects in under budget). Those closest to him would remark that Van Dyke’s death affected Mayer even more than Irving Thalberg’s.

His African adventures in making Trader Horn (1931) inspired the creation of Carl Denham, the fictitious director in King Kong (1933).

In her December 1972 Film Fan interview, Madge Evans gives the following appreciation of Van Dyke and his working methods: “A lot of people found Woody Van Dyke difficult, but I didn’t. I liked him very much, and I liked making films with him because he had been a cutter and his great position at the studio came about because he brought in his pictures so fast. He never took ten shots of anything. He never let a scene run over, because he could cut with the camera.”