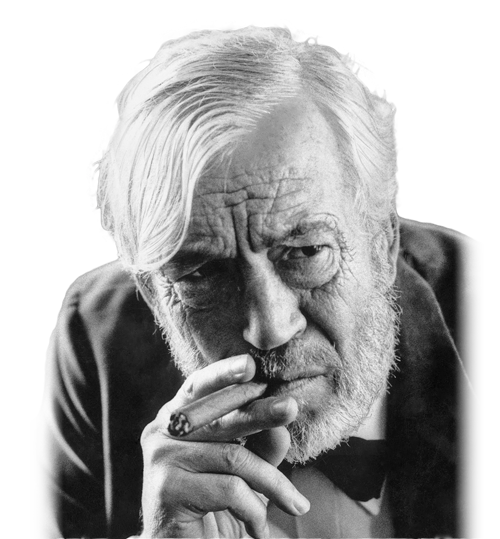

John Huston

Best known for the many classic American films he wrote and directed, including The Maltese Falcon (1941), The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), Key Largo (1948), The Asphalt Jungle (1950), The African Queen (1951), Moulin Rouge (1952), The Misfits (1961), and The Man Who Would Be King (1975). In his 46-year career, Huston received 15 Oscar nominations, won twice, and directed both his father, Walter Huston, and daughter, Anjelica Huston, to Oscar wins in different films.

John Marcellus Huston was born on August 5, 1906, in Nevada, Missouri. He was the only child of Rhea (née Gore) and Canadian-born Walter Huston, originally Walter Houghston. His father was an actor, initially in vaudeville, and later in films. His mother initially worked as a sports editor for various publications but gave it up after Huston was born. Similarly, his father gave up his stage acting career for steady employment as a civil engineer, although he returned to stage acting within a few years. He would later become highly successful on both Broadway and then in motion pictures. He had Scottish, Scots-Irish, English and Welsh ancestry.

Huston’s parents divorced in 1913, when he was 6, and as a result much of his childhood was spent in boarding schools. During summer vacations, he traveled with each of his parents separately — with his father on vaudeville tours, and with his mother to racetracks or other sports events. The young Huston benefited greatly from seeing his father act on stage, as he was later drawn to the world of acting.

As a child he was often ill and was treated for an enlarged heart and kidney ailments. He recovered after an extended bedridden stay in Arizona, and moved with his mother to Los Angeles, where he went to Lincoln Heights High School. He dropped out of high school after two years to become a professional boxer, and by age 15 was already a top-ranking amateur lightweight boxer in California. He ended his brief boxing career after suffering a broken nose.

He plunged himself into a wide variety of interests, including abstract painting, ballet, English and French literature, opera, and horseback riding. Living in Los Angeles he became “infatuated” with the new film industry and motion pictures, but as a spectator only. To Huston, “Charlie Chaplin was a god.”

He moved back to New York to live with his father, who was then acting in off-Broadway productions, and John had a few small roles. He remembers, while watching his father rehearse, being fascinated with the mechanics of acting:

What I learned there, during those weeks of rehearsal, would serve me for the rest of my life.

After a short period acting on stage, and having undergone surgery, he traveled on his own to Mexico. During his two years there, among his other adventures, he got a position riding as an honorary member of the Mexican cavalry. He returned to Los Angeles and married a girlfriend from high school, Dorothy Harvey. Their marriage lasted seven years.

During his stay in Mexico, he wrote a play called “Frankie and Johnny”, based on the ballad of the same title. After selling it easily, he decided that writing would be a viable career, and he focused on it. His self-esteem was boosted when H. L. Mencken, editor of the popular magazine American Mercury, bought two of his stories, “Fool” and “Figures of Fighting Men.” In subsequent years his stories and feature articles were published in Esquire, Theatre Arts, and The New York Times. In 1931, when he was 25, he moved back to Los Angeles with his hopes set on writing for the blossoming film industry, where the silent film industry had given way to “talkies”, and writers were in demand. In addition, his father had earlier moved there and had already been successful in a number of films.

He received a script editing contract with Samuel Goldwyn Productions, but after six months of receiving no assignments, quit to work for Universal Studios, where his father was by then a star. At Universal, he got a job in the script department, and began by writing dialogue for a number of films in 1932, including Murders in the Rue Morgue, A House Divided, and Law and Order. The last two also starred his father. In addition, House Divided was directed by William Wyler, who gave Huston his first real “inside view” of the filmmaking process during all stages of production. Wyler and Huston would later become close friends and collaborators on a number of leading films.

Huston gained a reputation as a “lusty, hard-drinking libertine” during his first years as a writer in Hollywood. He describes those years as a “series of misadventures and disappointments”, however. His brief career as a Hollywood writer ended suddenly after a car he was driving struck and killed a young female pedestrian. He was absolved of blame by a coroner’s jury, but the incident left him traumatized, and he moved to London and Paris, where he lived as a drifter.

By 1937, after five years, the 31-year-old Huston returned to Hollywood intent on being a “serious writer.” He also married Lesley Black. His first job was as scriptwriter with Warner Brothers Studio, with his personal longterm goal of directing his own scripts. For the next four years, he co-wrote scripts for major films such as Jezebel, The Amazing Dr. Clitterhouse, Juarez, Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet and Sergeant York (1941). He was nominated for an Academy Award for his writing both Ehrlich and York. Huston writes that Sergeant York, which was directed by Howard Hawks, has “gone down as one of Howard’s best pictures, and Gary Cooper had a triumph playing the young mountaineer.”

Huston was becoming a recognized and respected screenwriter, and persuaded Warners to give him a chance to direct, under the condition that his next script also became a hit. Huston writes:

They indulged me rather. They liked my work as a writer and they wanted to keep me on. If I wanted to direct, why, they’d give me a shot at it, and if it didn’t come off all that well, they wouldn’t be too disappointed as it was to be a very small picture.

The next script he was given to work on was High Sierra (1941), to be directed by Raoul Walsh. The film became the hit Huston wanted. It also made Humphrey Bogart a star with his first major role, as a gunman on the run. Warners kept their end of the bargain, and gave Huston his choice of subject.

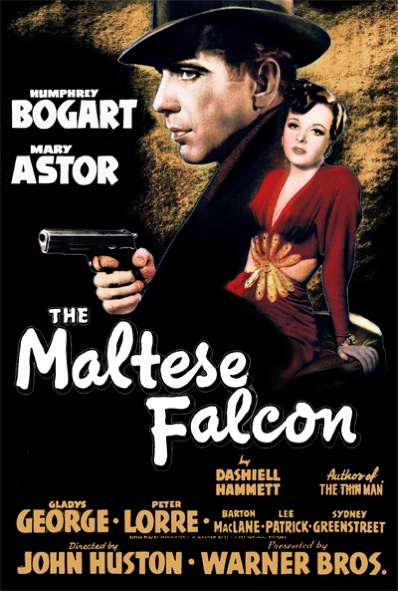

For his first directing assignment, Huston chose Dashiell Hammett’s detective thriller, The Maltese Falcon, films of which had already failed twice at the box office. However, studio head Jack L. Warner approved of Huston’s treatment of Hammett’s 1930 novel.

Huston kept the screenplay close to the novel, preserving much of Hammett’s dialogue, and directing it in an uncluttered style, much like the book’s narrative. He also did the unusual preparation for this, his first directing job, by sketching out each shot beforehand, including camera positions, lighting, and compositional scale.

Crucially, he selected a superior cast, giving Humphrey Bogart the lead role. Bogart was happy to take it, as he liked working with Huston. In addition, the supporting cast included other noted actors: Mary Astor, Peter Lorre, Sydney Greenstreet (in his first film role), and his own father, Walter Huston. The film, however, was given only a small B-movie budget, and received minimal publicity from Warners, as they had low expectations. The film was made in eight weeks for only $300,000.

Upon receiving immediate enthusiastic response by the public and critics, Warners was surprised. Critics hailed the film as a “classic”, and up until the present day it is considered by many to be the “best detective melodrama ever made.” Herald Tribune critic Howard Barnes called it a “triumph.” Huston again received an Academy Award nomination for the screenplay. After this film, Huston would from then on direct all of his screenplays, except for one, Three Strangers (1946). In 1942, he directed two more hits, In This Our Life (1942), starring Bette Davis, and Across the Pacific, another thriller starring Humphrey Bogart.

In 1942 he served in the United States Army for World War II to make films for the Army Signal Corps. While in uniform with the rank of captain, he directed and produced three films that some critics rank as “among the finest made about World War II: Report from the Aleutians (1943), about soldiers preparing for combat; The Battle of San Pietro (1945), the story (censored by the Army) of a failure by America’s intelligence agencies which resulted in many deaths, and Let There Be Light (1946), about psychologically damaged veterans, also censored for 35 years, until 1981. He rose to the rank of major and received the Legion of Merit award for “courageous work under battle conditions.” Nonetheless, all of his films made for the Army were “controversial”, and were either not released, censored, or banned outright, as they were considered “demoralizing” to soldiers and the public. Years later, after moving to Ireland, his daughter, actress Anjelica Huston, recalled that the “main movies we watched were the war documentaries.”

Huston did an uncredited rewrite of Anthony Veiller’s screenplay for The Stranger (1946), a film he was to have directed. When Huston became unavailable Orson Welles was offered the opportunity to direct. He had been cast in the role of a high-ranking Nazi fugitive who manages to settle in New England under an assumed name.

Houston’s next picture, which he wrote, directed, and briefly appeared in as an American, asked to “help out a fellow American, down on his luck”, was The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948). It would become one of his works which established his reputation as a leading filmmaker. The film, also starring Humphrey Bogart, was the story of three drifters who band together to prospect for gold. Huston also gave a supporting role to his father.

Warners was initially uncertain what to make of the film. They had allowed Huston to film on location in Mexico, considered a “radical move” at the time. They also knew that Huston was gaining a reputation as “one of the wild men of Hollywood.” In any case, Jack L. Warner initially “detested it.” But upon its release the film achieved widespread public and critical acclaim. Hollywood writer James Agee called it “one of the most beautiful and visually alive movies I have ever seen.” Time magazine described it as “one of the best things Hollywood has done since it learned to talk.” Huston won Oscars for Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay; his father won for Best Supporting Actor. It also won other awards in the U.S. and overseas.

Huston moved on quickly to Key Largo, again with Humphrey Bogart starring. It was the story about a disillusioned returning war veteran clashing with gangsters on a remote Florida key. It co-starred Lauren Bacall, Claire Trevor, Edward G. Robinson, and Lionel Barrymore. An adaptation of the stage play by Maxwell Anderson, the film seemed overly stage-bound for many viewers, but the “outstanding performances” by all the actors saved the day, and Claire Trevor won an Oscar for best supporting actress. Huston was annoyed that the studio cut several scenes from the final release without his consent. That, and other disputes, angered Huston enough that he left the studio when his contract expired.

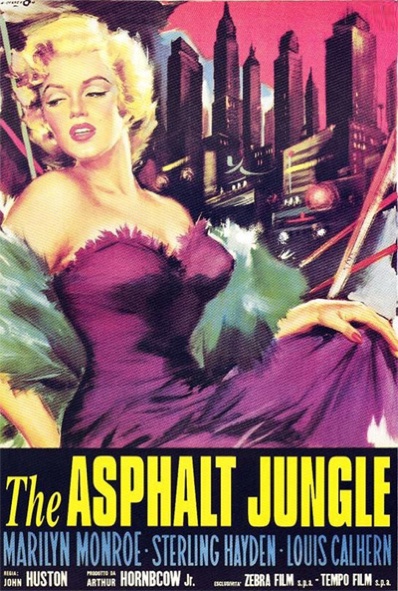

In 1950 he wrote and directed The Asphalt Jungle, a film which broke new ground by depicting criminals somewhat sympathetically, simply doing their professional work, “an occupation like any other”, or what Huston calls “a left-handed form of human endeavor.” Huston gave “deep attention” to the plot, involving a large jewelry theft, by examining the minute, step-by-step details and difficulties each of the characters encountered while carrying it out. Some critics opined that Huston had achieved an almost “documentary” style.

Andrew Sarris considered it to be “Huston’s best film”, and the film that made Marilyn Monroe a respected actress.

The Asphalt Jungle starred Sterling Hayden and Huston’s personal friend, Sam Jaffe. It also became the first serious role for Marilyn Monroe, according to Huston: “it was, of course, where Marilyn Monroe got her start.” The film succeeded at the box office and Huston was again nominated for Best Screenplay and Best Director Oscars, along with winning a Screen Directors Guild Award.

After completing The Asphalt Jungle, Huston’s next film, The Red Badge of Courage (1951), took on the subject of war and its effect on soldiers. While in the army during World War II, Houston had become interested in Stephen Crane’s classic American Civil War novel. For the starring role, Huston chose World War II hero Audie Murphy to play the young Union soldier who deserts his company out of fear, but later returns to fight alongside them. MGM executives, however, saw the message of the movie as too antiwar. Without Huston’s input, they cut down the running time of the film from eighty-eight minutes to sixty-nine, added narration, and deleted what Huston felt was a crucial scene.

The movie did poorly at the box office. Huston suggests that it “brought war very close to home.” He recalled that at a preview, before the film was halfway through, “damn near a third of the audience got up and walked out of the theater.” Despite the “butchering” and weak public response, film historian Michael Barson describes the movie as “a minor masterpiece.”

Before The Asphalt Jungle opened in theaters, Huston was in Africa shooting The African Queen (1951), a story based on C. S. Forester’s popular novel. It starred Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn in a combination of romance, comedy and adventure. The film’s producer, Sam Spiegel, urged Huston to change the ending to allow the protagonists to survive. Huston agreed, and the ending was rewritten. It became Huston’s most successful film financially, and “it remains one of his finest works.” Huston was nominated for two Academy Awards — Best Director and Best Screenplay, but won neither. Bogart, however, won an Oscar for Best Actor, his first.

In 1952 Huston moved to Ireland as a result of his disgust over the “witch-hunt” and “moral rot” he felt was created by House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC), which had affected many of his friends in the movie industry. Huston had, with friends including director William Wyler and screenwriter Philip Dunne, established the “Committee for the First Amendment”, as a response to government investigations into communists within the film industry. The HUAC called numerous filmmakers, screenwriters, and actors to testify about any past affiliations. Houston described the types of people who were alleged communists:

The people who did get caught up in it were, for the most part, well-intentioned boobs from a poor background. A number of them had come from the Lower East Side of Manhattan, and out in Hollywood, they sort of felt guilty for living the good life. Their social conscience was more acute than the next fellow’s.

Huston took producing, writing, and directing credits for his next two films: Moulin Rouge (1953); and Beat the Devil (1953). Moby Dick (1956), however, was written by Ray Bradbury, although Huston had his name added to the screenplay after the completion of the project. Although Huston had personally hired Bradbury to adapt Herman Melville’s novel into a screenplay, Bradbury and Huston did not get along during pre-production, and Bradbury later dramatized their relationship in the short story “Banshee”; Peter O’Toole would later play the John Huston role when “Banshee” was dramatized.

Huston had been planning to film Moby Dick for the previous ten years, and originally saw it as an excellent part for his father, Walter Huston. When his father died in 1950, he chose Gregory Peck to play Captain Ahab. The movie was filmed over a three-year period on location in Ireland, where Huston was then living. The fishing village of New Bedford, Massachusetts was recreated along the waterfront; the sailing ship in the film was fully constructed to be seaworthy; and three 100-foot whales were built out of steel, wood, and plastic. The film failed at the box office though, as well as with some critics, like David Robinson, who suggested that the movie lacked the “mysticism of the book.”

Of his next five films, only The Misfits (1961) found critical approval. However, critics have noted the “retrospective atmosphere of doom” which now hangs over the film. Clark Gable, the star, died of a heart attack a few days after the filming was completed; Marilyn Monroe never did another film and died a year later; and costars Montgomery Clift and Thelma Ritter also died over the next few years. During the filming itself, Monroe was often on drugs, was often late on the set and often forgot her lines. Her problems also led to the breakup of her marriage to the film’s scriptwriter, Arthur Miller, “virtually on set.” Huston later commented about this period in her career: “Marilyn was on her way out. Not only of the picture, but of life.”

He followed The Misfits with Freud: The Secret Passion, a film quite different from most of his others. Besides directing, he also narrates portions of the story. Film historian Stuart M. Kaminsky notes that Huston presents Sigmund Freud, played by Montgomery Clift, “as a kind of savior and messiah”, with an “almost Biblical detachment.” As the film begins, Huston describes Freud as a “kind of hero or God on a quest for mankind”:

This is the story of Freud’s descent into a region as black as hell, man’s unconscious, and how he let in the light.

Huston explains how he became interested in psychotherapy, the subject of the film:

I first got into that through an experience in a hospital during the war, where I made a documentary about patients suffering from battle neuroses. I was in the army and made the picture “Let There Be Light”. That experience started my interest in psychotherapy, and to this day Freud looms as the single huge figure in that field.

For his next film, Huston once again traveled to Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, after meeting an architect by the name of Guillermo Wulff, who owned property and businesses in the town. Filming took place in a beach cove called Mismaloya, about thirty minutes south of town. Huston adapted the stage play by Tennessee Williams. The film stars Richard Burton and Ava Gardner, and was nominated for several Academy Awards. Production attracted intense worldwide media attention, due to Burton bringing his celebrity mistress Elizabeth Taylor (who was married to singer Eddie Fisher at the time) to the production. Huston liked Puerto Vallarta so much that he bought a house nearby, as did Burton and Taylor. Guillermo Wulff and Huston became friends and spent time with him whenever Huston was in town.

Producer Dino De Laurentis journeyed to Ireland to ask Huston to direct what turned out to be his next project — The Bible: In the Beginning. Although De Laurentis had ambitions for a broader story, he realized that the subject could not be adequately covered and limited The Bible to the first half of the Book of Genesis. Huston enjoyed directing the film, as it gave him a chance to indulge his love of animals. Besides directing he also played the role of Noah and the voice of God. The film did poorly at the box office, however, and at a cost of 18 million dollars, it was the most expensive movie in his career. Huston added these details about the filming:

Every morning before beginning work, I visited the animals. One of the elephants, Candy, loved to be scratched on the belly behind her foreleg. I’d scratch her and she would lean farther and farther toward me until there was some danger of her toppling over on me. One time I started to walk away from her, and she reached out and took my wrist with her trunk and pulled me back to her side. It was a command: “Don’t stop!” I used it in the picture. Noah scratches the elephant’s belly and walks away, and the elephant pulls him back to her time after time.

After several films that were not well received, Huston returned to critical acclaim with Fat City. Based on Leonard Gardner’s 1969 novel of the same name, it told the story of an aging, washed-up alcoholic boxer trying to get his name back on the map, while having a new relationship with a world weary alcoholic, and an amateur boxer trying to find success in boxing. The film was nominated for several awards. It starred Stacy Keach, a young Jeff Bridges, and Susan Tyrrell, who was nominated for a Best Supporting Actress Oscar. Roger Ebert called Fat City one of Huston’s best films.

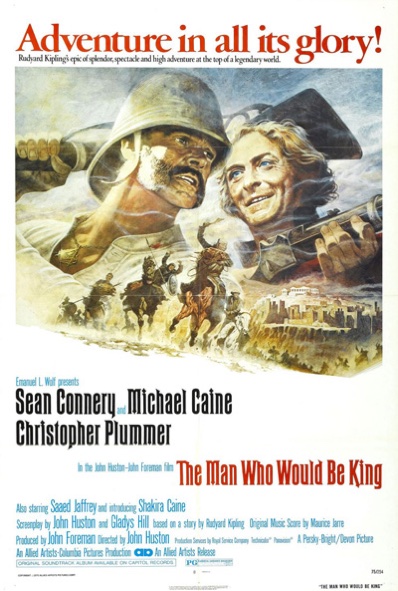

Perhaps Huston’s most highly regarded film of the 1970s, The Man Who Would Be King was both a critical and commercial success. Huston had been planning to make it since the ’50s, originally with Humphrey Bogart and Clark Gable. Eventually the lead roles went to Sean Connery and Michael Caine. The movie was filmed on location in North Africa and praised for its use of old fashioned escapism and entertainment. Steven Spielberg has cited the film as one of his inspirations for Raiders of the Lost Ark.

After filming The Man Who Would Be King, Huston took his longest hiatus from directing. He returned with an offbeat and somewhat controversial film based on the novel Wise Blood.

Huston’s next film, Under the Volcano, was set in Mexico and starred Albert Finney as an alcoholic ambassador at the beginning of World War II. Grim and brilliant, it is held in high regard by critics.

John Huston’s final film, The Dead, is an adaptation of the classic short story by James Joyce. It may have been one of Huston’s most personal films, due to his Irish ancestry and his passion for classic literature. He directed most of it from a wheelchair, as he needed an oxygen tank to breathe in the last few months of his life. The film was nominated for two Academy Awards, and was praised by critics. Roger Ebert eventually placed it in his Great Movies list. Huston died four months before the film’s release date.

John Huston’s directing credits include…

| Year | Movie |

|---|---|

| 1987 | The Dead |

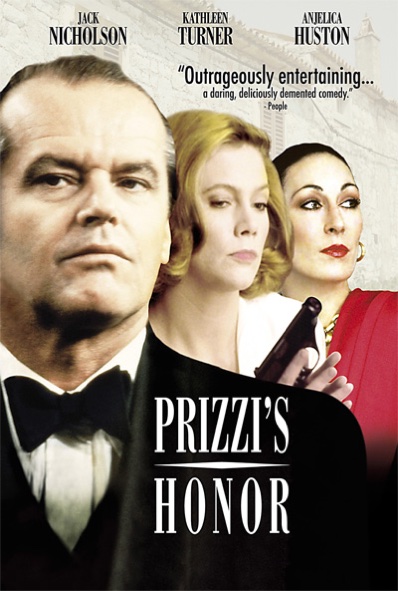

| 1985 | Prizzi’s Honor |

| 1984 | Under the Volcano |

| 1982 | Annie |

| 1981 | Victory |

| 1980 | Phobia |

| 1979 | Wise Blood (as John Huston) |

| 1979 | Love and Bullets (uncredited) |

| 1976 | Independence (Short) |

| 1975 | The Man Who Would Be King |

| 1973 | The MacKintosh Man |

| 1972 | The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean |

| 1972 | Fat City |

| 1971 | The Last Run (uncredited) |

| 1970 | The Kremlin Letter |

| 1969 | A Walk with Love and Death |

| 1969 | Sinful Davey |

| 1967 | Reflections in a Golden Eye |

| 1967 | Casino Royale (scenes at Sir James Bond’s house and castle in Scotland scenes) |

| 1966 | The Bible: In the Beginning… |

| 1964 | The Night of the Iguana |

| 1963 | The List of Adrian Messenger |

| 1962 | Freud |

| 1961 | The Misfits |

| 1960 | The Unforgiven |

| 1958 | The Roots of Heaven |

| 1958 | The Barbarian and the Geisha |

| 1957 | A Farewell to Arms (uncredited) |

| 1957 | Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison |

| 1956 | Moby Dick |

| 1953 | Beat the Devil |

| 1952 | Moulin Rouge |

| 1951 | The African Queen |

| 1951 | The Red Badge of Courage |

| 1950 | The Asphalt Jungle |

| 1949 | We Were Strangers |

| 1948 | Key Largo |

| 1948 | On Our Merry Way (uncredited) |

| 1948 | The Treasure of the Sierra Madre |

| 1946 | Let There Be Light (Documentary) |

| 1945 | San Pietro (Documentary short) (uncredited) |

| 1944 | Tunisian Victory (Documentary) (replacement scenes) |

| 1943 | Report from the Aleutians (Documentary) (uncredited) |

| 1942 | Across the Pacific |

| 1942 | Winning Your Wings (Short) |

| 1942 | In This Our Life |

| 1941 | The Maltese Falcon |

Memorable Quotes by John Huston

“I’ve lived a number of lives. I’m inclined to envy the man who leads one life, with one job, and one wife, in one country, under one God. It may not be a very exciting existence, but at least by the time he’s seventy-three he knows how old he is.”

[On remakes] “There is a willful lemming-like persistence in remaking past successes time after time. They can’t make them as good as they are in our memories, but they go on doing them and each time it’s a disaster. Why don’t we remake some of our bad pictures — I’d love another shot at ‘Roots of Heaven’ — and make them good?”

“Half of directing is casting the right actors.”

“The directing of a picture involves coming out of your individual loneliness and taking a controlling part in putting together a small world. A picture is made. You put a frame around it and move on. And one day you die. That is all there is to it.”

[on Jack Nicholson] “I have great respect for him. Not only as an artist but as an individual. He has a fine eye for good paintings and a good ear for fine music. And he’s a lovely man to drink with. A boon companion! I’d like to make more pictures with Jack Nicholson.”

“I think the worst thing I ever saw Brando do was Apocalypse Now (1979), which was just dreadful — the finish of that picture. The model for it, Heart of Darkness, has no finish either, and the movie-makers just didn’t find one either. It’s very good for a picture to have an ending before you start shooting!”

Things You May Not Know About John Huston

At one time he kept a pet monkey. His wife of the time, Evelyn Keyes, became fed up with the noise and the mess and told Huston that either she or the monkey would have to leave. “Honey,” replied Huston, “it’s you!”

He is the only person to have ever directed a parent (Walter Huston) and a child (Anjelica Huston) to Academy Award wins.

He was a licensed pilot… and a prankster. He once flew over a golf course and dropped 5,000 ping-pong balls while a celebrity golf tournament was in progress.

After he and wife Ricki separated, she became pregnant by another man. When she died, Huston brought her daughter, Allegra Huston, to live with him and adopted her.

He once described Charles Bronson as “a grenade with the pin pulled”.

His WW II documentary Let There Be Light (1946) was one of the first, if not the first, films to deal with the issue of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder of soldiers returning from the war. Huston actually said that, “If I ever do a movie that glorifies war, somebody shoot me.” This documentary was based on his front-line experiences covering the European war and what he saw soldiers go through during and returning from the war.