John Ford

Best known for directing many classic American Westerns, such as Stagecoach (1939), The Searchers (1956), and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), as well as adaptations of classic 20th-century American novels such as the film The Grapes of Wrath (1940). His four Academy Awards for Best Director (in 1935, 1940, 1941, and 1952) are still a record. One of the films for which he won the award, How Green Was My Valley, also won Best Picture.

In a career that spanned more than 50 years, Ford directed more than 140 films (although most of his silent films are now lost) and he is widely regarded as one of the most important and influential film-makers of his generation. Ford’s work was held in high regard by his colleagues, with Orson Welles and Ingmar Bergman among those who have named him one of the greatest directors of all time.

Ford made frequent use of location shooting and long shots, in which his characters were framed against a vast, harsh and rugged natural terrain.

John Ford was born John Martin “Jack” Feeney (though he later often gave his given names as Sean Aloysius, sometimes with surname O’Feeny or O’Fearna; an Irish language equivalent of Feeney) in Cape Elizabeth, Maine to John Augustine Feeney and Barbara “Abbey” Curran, on February 1, 1894 (though he occasionally said 1895 and that date is erroneously inscribed on his tombstone). His father, John Augustine, was born in Spiddal, County Galway, Ireland in 1854. Barbara Curran had been born in the Aran Islands, in the town of Kilronan on the island of Inishmore (Inis Mór). John A. Feeney’s grandmother, Barbara Morris, was said to be a member of a local (impoverished) gentry family, the Morrises of Spiddal.

John Augustine and Barbara Curran arrived in Boston and Portland respectively in May and June 1872. They married in 1875 and became American citizens five years later on September 11, 1880. They had eleven children: Mamie (Mary Agnes), born 1876; Delia (Edith), 1878–1881; Patrick; Francis Ford, 1881–1953; Bridget, 1883–1884; Barbara, born and died 1888; Edward, born 1889; Josephine, born 1891; Hannah (Joanna), born and died 1892; John Martin, 1894–1973; and Daniel, born and died 1896 (or 1898). John Augustine lived in the Munjoy Hill neighborhood of Portland, Maine with his family, and would try farming, fishing, working for the gas company, running a saloon, and being an alderman.

Feeney attended Portland High School, Portland, Maine, where he was a successful fullback and defensive tackle. He earned the nickname “Bull” because of the way he would lower his helmet and charge the line. A Portland pub is named Bull Feeney’s in his honor. He later moved to California and in 1914 began working in film production as well as acting for his older brother Francis, adopting “Jack Ford” as a professional name. In addition to credited roles, he appeared uncredited as a Klansman in D. W. Griffith’s 1915 The Birth of a Nation, as the man who lifts up one side of his hood so he can see clearly.

He married Mary McBride Smith on July 3, 1920, and they had two children. The marriage between Ford and Smith lasted for life despite various issues, one of which could have proved problematic from the start, this being that John Ford was Catholic while she was a non-Catholic divorcée. What difficulty was caused by the two marrying is unclear as the level of John Ford’s commitment to the Catholic faith is disputed. A strain would have been Ford’s many extramarital relationships.

John Ford began his career in film after moving to California in July 1914. He followed in the footsteps of his multi-talented older brother Francis Ford, twelve years his senior, who had left home years earlier and had worked in vaudeville before becoming a movie actor. Francis played in hundreds of silent pictures for filmmakers such as Thomas Edison, Georges Méliès and Thomas Ince, eventually progressing to become a prominent Hollywood actor-writer-director with his own production company (101 Bison) at Universal.

John Ford started out in his brother’s films as an assistant, handyman, stuntman and occasional actor, frequently doubling for his brother, whom he closely resembled. Francis gave his younger brother his first acting role in The Mysterious Rose (November 1914). Despite an often combative relationship, within three years Jack had progressed to become Francis’ chief assistant and often worked as his cameraman. By the time Jack Ford was given his first break as a director, Francis’ profile was declining and he ceased working as a director soon after.

One notable feature of John Ford’s films is that he used a ‘stock company’ of actors, far more so than many directors. Many famous stars appeared in at least two or more Ford films, including Harry Carey, Sr., (the star of 25 Ford silent films), Will Rogers, John Wayne, Henry Fonda, Maureen O’Hara, James Stewart, Woody Strode, Richard Widmark, Victor McLaglen, Vera Miles and Jeffrey Hunter. Many of his supporting actors appeared in multiple Ford films, often over a period of several decades, including Ben Johnson, Chill Wills, Andy Devine, Ward Bond, Grant Withers, Mae Marsh, Anna Lee, Harry Carey, Jr., Ken Curtis, Frank Baker, Dolores del Río, Pedro Armendáriz, Hank Worden, John Qualen, Barry Fitzgerald, Arthur Shields, John Carradine, O.Z. Whitehead and Carleton Young. Core members of this extended ‘troupe’, including Ward Bond, John Carradine, Harry Carey, Jr., Mae Marsh, Frank Baker and Ben Johnson, were informally known as the John Ford Stock Company.

Likewise, Ford enjoyed extended working relationships with his production team, and many of his crew worked with him for decades. He made numerous films with the same major collaborators, including producer and business partner Merian C. Cooper, scriptwriters Nunnally Johnson, Dudley Nichols and Frank S. Nugent, and cinematographers Ben F. Reynolds, John W. Brown and George Schneiderman (who between them shot most of Ford’s silent films), Joseph H. August, Gregg Toland, Winton Hoch, Charles Lawton Jr., Bert Glennon, Archie Stout and William H. Clothier.

During his first decade as a director Ford honed his craft on dozens of features (including many westerns) but only ten of the more than sixty silent films he made between 1917 and 1928 survived in their entirety. However, prints of several Ford ‘silents’ previously thought lost have been rediscovered in foreign film archives over recent years — in 2009 a trove of 75 Hollywood silent films was rediscovered in the New Zealand Film Archive, among which was the only surviving print of Ford’s 1927 silent comedy Upstream.

Throughout his career Ford was one of the busiest directors in Hollywood, but he was extraordinarily productive in his first few years as a director — he made ten films in 1917, eight in 1918 and fifteen in 1919 — and he directed a total of 62 shorts and features between 1917 and 1928, although he was not given a screen credit in most of his earliest films.

There is some uncertainty about the identity of Ford’s first film as director — film writer Ephraim Katz notes that Ford might have directed the four-part film Lucille the Waitress as early as 1914 — but most sources cite his directorial début as the silent two-reeler The Tornado, released in March 1917. According to Ford’s own story, he was given the job by Universal boss Carl Laemmle who supposedly said, “Give Jack Ford the job — he yells good”. The Tornado was quickly followed by a string of two-reeler and three-reeler “quickies” — The Trail of Hate, The Scrapper, The Soul Herder and Cheyenne’s Pal; these were made over the space of a few months and each typically shot in just two or three days; all are now presumed lost. The Soul Herder is also notable as the beginning of Ford’s four-year, 25-film association with writer-actor Harry Carey, who was a strong early influence on the young director, as well as being one of the major influences on the screen persona of Ford’s protege John Wayne. Carey’s son Harry “Dobe” Carey Jr, who also became an actor, was one of Ford’s closest friends in later years and featured in many of his most celebrated westerns.

Ford’s first feature-length production was Straight Shooting (August 1917), which is also his earliest complete surviving film as director, and one of only two survivors from his twenty-five film collaboration with Harry Carey. In making the film Ford and Carey ignored studio orders and turned in five reels instead of two, and it was only through the intervention of Carl Laemmle that the film escaped being cut for its first release, although it was subsequently edited down to two reels for re-release in the late 1920s. Ford’s last film of 1917, Bucking Broadway, was long thought to have been lost, but in 2002 the only known surviving print was discovered in the archives of the French National Center for Cinematography and it has since been restored and digitized.

Ford directed around thirty-six films over three years for Universal before moving to the William Fox studio in 1920; his first film for them was Just Pals (1920). His 1923 feature Cameo Kirby, starring screen idol John Gilbert—another of the few surviving Ford silents—marked his first directing credit under the name “John Ford”, rather than “Jack Ford”, as he had previously been credited.

Ford’s first major success as a director was the historical drama The Iron Horse (1924), an epic account of the building of the First Transcontinental Railroad. It was a large, long and difficult production, filmed on location in the Sierra Nevada. The logistics were enormous—two entire towns were constructed, there were 5000 extras, 100 cooks, 2000 rail layers, a cavalry regiment, 800 Indians, 1300 buffalo, 2000 horses, 10,000 cattle and 50,000 properties, including the original stagecoach used by Horace Greeley, Wild Bill Hickok’s derringer pistol and replicas of the “Jupiter” and “119” locomotives that met at Promontory Point when the two ends of the line were joined on 10 May 1869.

Ford’s brother Eddie was a crew member and they fought constantly; on one occasion Eddie reportedly “went after the old man with a pick handle”. There was only a short synopsis written when filming began and Ford wrote and shot the film day by day. Production fell behind schedule, delayed by constant bad weather and the intense cold, and Fox executives repeatedly demanded results, but Ford would either tear up the telegrams or hold them up and have stunt gunman Edward “Pardner” Jones shoot holes through the sender’s name. Despite the pressure to halt the production, studio boss William Fox finally backed Ford and allowed him to finish the picture and his gamble paid off handsomely—The Iron Horse became one of the top-grossing films of the decade, taking over US$2 million worldwide, against a budget of $280,000.

Ford made a wide range of films in this period, and he became well known for his Western and ‘frontier’ pictures, but the genre rapidly lost its appeal for major studios in the late 1920s. Ford’s last silent Western was 3 Bad Men (1926), set during the Dakota land rush and filmed at Jackson Hole, Wyoming and in the Mojave Desert. It would be thirteen years before he made his next Western, Stagecoach, in 1939.

Ford was one of the pioneer directors of sound films; he shot Fox’s first song sung on screen, for his film Mother Machree (1928) of which only three of the original seven reels survive; this film is also notable as the first Ford film to feature the young John Wayne (as an uncredited extra) and he appeared in Ford’s next two films. Ford also directed Fox’s first all-talking dramatic feature Napoleon’s Barber (1928), a 3-reeler which is also now lost.

Just before the studio converted to talkies, Fox gave a contract to the German director F. W. Murnau, and his film Sunrise (1927), still highly regarded by critics, had a powerful effect on Ford. Murnau’s influence can be seen in many of Ford’s films of the late 1920s and early 1930s — his penultimate silent feature Four Sons (1928), was filmed on some of the lavish sets left over from Murnau’s production. Ford’s last silent feature Hangman’s House (1928) is notable as one of the first credited screen appearances by John Wayne.

Napoleon’s Barber was followed by Riley the Cop (1928) and Strong Boy (1929), starring Victor McLaglen; the latter is now lost (although Tag Gallagher’s book records that the only surviving copy of Strong Boy, a 35 mm nitrate print, was rumored to be held in a private collection in Australia). The Black Watch (1929), a colonial army adventure set in the Khyber Pass starring Victor McLaglen and Myrna Loy is Ford’s first complete surviving talking picture; it was remade in 1954 by Henry King as King of the Khyber Rifles.

Ford’s output was fairly constant from 1928 to the start of World War II; he made five features in 1928 and then made either two or three films every year from 1929 to 1942, inclusive. Three films were released in 1929 — Strong Boy, The Black Watch and Salute. His three films of 1930 were Men Without Women, Born Reckless and Up the River, which is notable as the debut film for both Spencer Tracy and Humphrey Bogart, who were both signed to Fox on Ford’s recommendation (but subsequently dropped). Ford’s films in 1931 were Seas Beneath, The Brat and Arrowsmith; the last-named, adapted from the Sinclair Lewis novel and starring Ronald Colman and Helen Hayes, marked Ford’s first Academy Awards recognition, with five nominations including Best Picture.

Ford’s efficiency and ability to craft films combining artfulness with strong commercial appeal won him growing renown. By 1940 he was acknowledged as one of the world’s foremost movie directors. His growing prestige was reflected in his remuneration — in 1920, when he moved to Fox, he was paid $300–600 per week. As his career took off in the mid-Twenties his annual income increased sharply. He earned nearly $134,000 in 1929, and made over $100,000 per annum every year from 1934 to 1941, earning a staggering $220,068 in 1938 — more than double the salary of the U.S. President at that time (although this was still less than half the income of Carole Lombard, Hollywood’s highest-paid star of the 1930s, who was earning around $500,000 per year at the time).

With film production affected by the Depression, Ford made two films each in 1932 and 1933 — Air Mail with a young Ralph Bellamy and Flesh with Wallace Beery.

The World War I desert drama The Lost Patrol (1934) was a superior remake of the similarly-titled 1929 silent film. It starred Victor McLaglen as The Sergeant — the role played by his brother Cyril McLaglen in the earlier version — with Boris Karloff, Wallace Ford, Alan Hale and Reginald Denny (who went on to found a company that made radio-controlled target aircraft during World War II). It was one of Ford’s first big hits of the sound era — it was rated by both the National Board of Review and The New York Times as one of the Top 10 films of that year and won an Oscar nomination for its Max Steiner score. It was followed later that year by The World Moves On with Madeleine Carroll and Franchot Tone, and the highly successful Judge Priest, his second film with Will Rogers, which became one of the top-grossing films of the year.

Ford’s first film of 1935 was the mistaken-identity comedy The Whole Town’s Talking with Edward G. Robinson and Jean Arthur, released in the UK as Passport to Fame, and it drew critical praise. Steamboat Round The Bend was his third and final film with Will Rogers; it is probable they would have continued working together, but their collaboration was cut short by Rogers’ untimely death in a plane crash in May 1935, which devastated Ford.

Ford confirmed his position in the top rank of American directors with the Murnau-influenced Irish Republican Army drama The Informer (1935), starring Victor McLaglen. It earned great critical praise, was nominated for Best Picture, won Ford his first Academy Award for Best Director, and was hailed at the time as one of the best films ever made, although its reputation has diminished considerably compared to other contenders like Citizen Kane, or Ford’s own later The Searchers (1956).

The politically charged The Prisoner of Shark Island (1936) — which marked the debut with Ford of long-serving “Stock Company” player John Carradine—explored the little-known story of Samuel Mudd, a physician who was caught up in the Abraham Lincoln assassination conspiracy and consigned to an offshore prison for treating the injured John Wilkes Booth. Other films of this period include the South Seas melodrama The Hurricane (1937) and the lighthearted Shirley Temple vehicle Wee Willie Winkie (1937), each of which had a first-year US gross of more than $1 million. During filming of Wee Willie Winkie, Ford had elaborate sets built on the Iverson Movie Ranch in Chatsworth, California, a heavily-filmed location ranch most closely associated with serials and B-Westerns, which would become, along with Monument Valley, one of the Ford’s preferred filming locations, and a site to which he would return in the next few years for Stagecoach and The Grapes of Wrath.

The longer revised version of Directed by John Ford shown on Turner Classic Movies in November, 2006 features directors Steven Spielberg, Clint Eastwood, and Martin Scorsese, who suggest that the string of classic films Ford directed during 1936 to 1941 was due in part to an intense six-month extra-marital affair with Katharine Hepburn, the star of Mary of Scotland (1936), an Elizabethan costume drama.

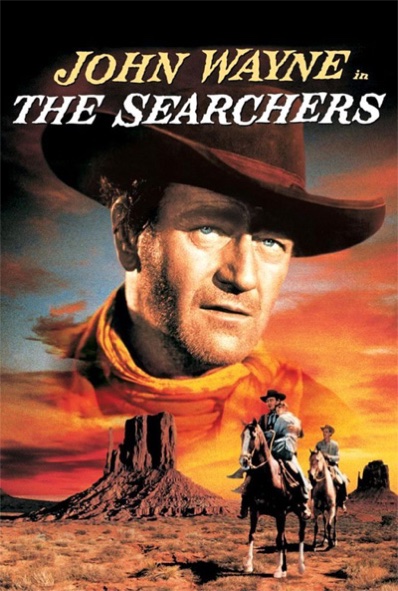

Stagecoach (1939) was Ford’s first western since 3 Bad Men in 1926, and it was his first with sound. Reputedly Orson Welles watched Stagecoach forty times in preparation for making Citizen Kane. It remains one of the most admired and imitated of all Hollywood movies, not least for its climactic stagecoach chase and the hair-raising horse-jumping scene, performed by renowned stuntman Yakima Canutt.

The Dudley Nichols–Ben Hecht screenplay was based on an Ernest Haycox story that Ford had spotted in Collier’s magazine and he purchased the screen rights for just $2500. Production chief Walter Wanger urged Ford to hire Gary Cooper and Marlene Dietrich for the lead roles, but eventually accepted Ford’s decision to cast Claire Trevor as Dallas and a virtual unknown, his friend John Wayne, as Ringo; Wanger reportedly had little further influence over the production.

In making Stagecoach, Ford faced deep industry prejudice about the now-hackneyed genre which, ironically, he had helped to make so popular. Although low-budget western features and serials were still being cranked out in large numbers by “Poverty Row” studios, the genre had fallen out of favor with the big studios in the 1930s and were regarded as B-grade “pulp” offerings at best. As a result, Ford shopped the project around Hollywood for almost a year, before he found a taker, Walter Wanger, an independent producer working through United Artists.

Stagecoach is significant for several reasons — it exploded industry prejudices by becoming both a critical and commercial hit, grossing over US$1 million in its first year (against a budget of just under $400,000), and its success (along with the 1939 Westerns Destry Rides Again with Dietrich and Michael Curtiz’s Dodge City with Erroll Flynn) revitalized the moribund genre, showing that Westerns could be “intelligent, artful, great entertainment — and profitable”. It was nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director, and won two Oscars, for Best Supporting Actor (Thomas Mitchell) and Best Score. Stagecoach became the first in the series of seven classic Ford Westerns filmed in Monument Valley, with additional footage shot at another of Ford’s favorite filming locations, the Iverson Movie Ranch in Chatsworth. Ford skillfully blended the Iverson and Monument Valley shots to create the movie’s iconic images of the American West.

John Wayne had good reason to be grateful for Ford’s support; Stagecoach gave him a career breakthrough that lifted him to stardom. Over 35 years Wayne appeared in 24 of Ford’s films and three television episodes. Ford played a major role in shaping Wayne’s screen image. Cast member Louise Platt, in a letter recounting the experience of the film’s production, quoted Ford saying of Wayne’s future in film: “He’ll be the biggest star ever because he is the perfect ‘everyman.'”

Stagecoach marked the beginning of the most consistently successful phase of Ford’s career — in just two years between 1939 and 1941 he directed a series of classics films that won numerous Academy Awards. Ford’s next film, the biopic Young Mr Lincoln (1939) starring Henry Fonda, was less successful than Stagecoach, attracting little critical attention and winning no awards. It was not a major box-office hit, although it racked up a respectable domestic first-year gross of $750,000, but Ford scholar Tag Gallagher describes it as “a deeper, more multi-leveled work than Stagecoach … (which) seems in retrospect one of the finest prewar pictures”.

Drums Along the Mohawk (1939) was a lavish frontier drama co-starring Henry Fonda and Claudette Colbert; it was also Ford’s first movie in color and included uncredited script contributions by William Faulkner. It was a big box-office success, grossing $1.25 million in its first year in the US and earning Edna May Oliver a Best Supporting Actress Oscar nomination.

Despite its uncompromising humanist and political stance, Ford’s screen adaptation of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (scripted by Nunnally Johnson and photographed by Gregg Toland) was both a big box office hit and a major critical success, and it is still widely considered one of the best Hollywood films of the era. Ford’s third movie in a year and his third consecutive film with Fonda, it grossed $1.1 million in the USA in its first year and won two Academy Awards — Ford’s second Best Director Oscar, and Best Supporting Actress for Jane Darwell’s tour-de-force portrayal of Ma Joad. During production, Ford returned to the Iverson Movie Ranch in Chatsworth to film a number of key shots, including the pivotal image depicting the migrant family’s first full view of the fertile farmland of California, represented by the San Fernando Valley as seen from the Iverson Ranch.

The Grapes of Wrath was followed by two less successful and lesser known films. The Long Voyage Home (1940) was, like Stagecoach, made with Walter Wanger through United Artists. Adapted from four plays by Eugene O’Neill, it was scripted by Dudley Nichols and Ford, in consultation with O’Neill. Although not a significant box-office success, it was critically praised and was nominated for seven Academy Awards — Best Picture, Best Screenplay, (Nichols), Best Music (Best Photography (Gregg Toland), Best Editing (Sherman Todd), Best Effects (Ray Binger & R.T. Layton), and Best Sound (Robert Parrish). It was one of Ford’s personal favorites; stills from it decorated his home and O’Neill also reportedly loved the film and screened it periodically.

Tobacco Road (1941) was a rural comedy scripted by Nunnally Johnson, adapted from the long-running Jack Kirkland stage version of the Erskine Caldwell novel. It starred veteran actor Charley Grapewin and the supporting cast included Ford regulars Ward Bond and Mae Marsh; it is also notable for early screen appearances by future stars Gene Tierney and Dana Andrews. Although not highly regarded by some critics, it was fairly successful at the box office.

Ford’s last feature before America entered World War II was his screen adaptation of How Green Was My Valley (1941), starring Walter Pidgeon, Maureen O’Hara and Roddy McDowell in his career-making role as Huw. The script was written by Philip Dunne from the best-selling novel by Richard Llewellyn. It was originally planned as a four-hour epic to rival Gone with the Wind — the screen rights alone cost Fox $300,000 — and was to have been filmed on location in Wales, but these plans were abandoned because of heavy German bombing of Britain. Another reported factor was the nervousness of Fox executives about the pro-union tone of the story. William Wyler was originally engaged to direct, but he left the project when Fox decided to film it in California; Ford was hired in his place and production was postponed for several months until he became available. Producer Darryl F. Zanuck had a strong influence over the movie and made several key decisions, including the idea of having the character of Huw narrate the film in voice-over (then a novel concept), and the decision that Huw’s character should not age (Tyrone Power was originally slated to play the adult Huw).

How Green Was My Valley became one of the biggest films of 1941. It was nominated for ten Academy Awards including Best Supporting Actress (Sara Allgood), Best Editing, Best Script, Best Music and Best Sound and it won five Oscars—Best Director, Best Picture, Best Supporting Actor (Donald Crisp), Best B&W Cinematography (Arthur C. Miller) and Best Art Direction/Interior Decoration. It was a huge hit with audiences, coming in behind Sergeant York as the second-highest grossing film of the year in the USA and taking almost $3 million against its sizable budget of $1,250,000. Ford was also named Best Director by the New York Film Critics, and this was one of the few awards of his career that he collected in person (he generally shunned the Oscar ceremony).

During World War II, Commander John Ford, USNR, served in the United States Navy and as head of the photographic unit for the Office of Strategic Services, made documentaries for the Navy Department. He won two more Academy Awards during this time, one for the semi-documentary The Battle of Midway (1942), and a second for the propaganda film December 7th (1943). Commander Ford was a veteran of the Battle of Midway, where he was wounded in the arm by shrapnel while filming the Japanese attack from the power plant of Sand Island on Midway.

Ford was also present on Omaha Beach on D-Day. He crossed the English Channel on the USS Plunkett (DD-431), anchored off Omaha Beach at 0600 where he observed the first wave land on the beach from the ship, landing on the beach himself later with a team of US Coast Guard cameramen who filmed the battle from behind the beach obstacles, with Ford directing operations. The film was edited in London, but very little was released to the public. Ford explained in a 1964 interview that the US Government was “afraid to show so many American casualties on the screen”, adding that all of the D-Day film “still exists in color in storage in Anacostia near Washington, D.C.” Thirty years later, historian Stephen E. Ambrose reported that the Eisenhower Center had been unable to find the film. According to records released in 2008, Ford was cited by his superiors for bravery, taking a position to film one mission that was “an obvious and clear target”. He survived “continuous attack and was wounded” while he continued filming, one commendation in his file states.

His last wartime film was They Were Expendable (1945), an account of America’s disastrous defeat in The Philippines, told from the viewpoint of a PT boat squadron and its commander. Ford created a part for the recovering Ward Bond, who needed money. Although he was seen throughout the movie, he never walked until they put in a part where he was shot in the leg. For the rest of the picture, he was able to use a crutch on the final march. Ford repeatedly declared that he disliked the film and had never watched it, complaining that he had been forced to make it. Released several months after the end of the war, it was among the year’s top 20 box-office draws.

After the war, Ford remained an officer in the United States Navy Reserve. He returned to active service during the Korean War, and was promoted to Rear Admiral the day he left.

Ford directed sixteen features and several documentaries between 1946 and 1956. As with his pre-war career, his films alternated between (relative) box office flops and major successes, but most of his later films were profitable, and Fort Apache, The Quiet Man, Mogambo and The Searchers all ranked in the Top 20 box-office hits of their respective years.

Ford’s first postwar movie My Darling Clementine (Fox, 1946) was a romanticized retelling of the primal Western legend of Wyatt Earp and the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, with exterior sequences filmed on location in the visually spectacular (if geographically inappropriate) Monument Valley. It reunited Ford with Henry Fonda (as Earp) and co-starred Victor Mature in one of his best roles as the consumptive, Shakespeare-loving Doc Holliday, with Ward Bond and Tim Holt as the Earp brothers, Linda Darnell as sultry saloon girl Chihuahua, a strong performance by Walter Brennan (in a rare villainous role) as the venomous Old Man Clanton, with Jane Darwell and an early screen appearance by John Ireland as Billy Clanton.

Refusing a lucrative contract offered by Zanuck at 20th Century Fox that would have guaranteed him $600,000 per year, Ford launched himself as an independent director-producer and made many of his films in this period with Argosy Pictures Corporation, which was a partnership between Ford and his old friend and colleague Merian C. Cooper. The Fugitive (1947), again starring Fonda, was its first project. It was a loose adaptation of Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory, which Ford originally intended to make at Fox before the war, with Thomas Mitchell as the priest. Filmed on location in Mexico, it was photographed by distinguished Mexican cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa. The supporting cast included Dolores del Río, J. Carrol Naish, Ward Bond, Leo Carrillo and Mel Ferrer in his screen début, with a cast of mostly Mexican extras. Ford reportedly considered this his best film but it fared relatively poorly commercially. It also caused a rift between Ford and scriptwriter Dudley Nichols that brought about the end of their highly successful collaboration. Greene himself had a particular dislike of this adaptation of his work.

Fort Apache (1948) was the first part of Ford’s so-called ‘Cavalry Trilogy’, all of which were based on stories by James Warner Bellah. It featured many of his ‘Stock Company’ of actors, including John Wayne, Henry Fonda, Ward Bond, Victor McLaglen, Mae Marsh, Francis Ford (as a bartender), Frank Baker, Ben Johnson and also featured Shirley Temple, in her final appearance for Ford and one of her last film appearances. It also marked the start of the long association between Ford and scriptwriter Frank S. Nugent, a former New York Times film critic who (like Dudley Nichols) had not written a movie script until being hired by Ford. It was a big commercial success, grossing nearly $5 million worldwide in its first year and ranking in the Top 20 box office hits of 1948.

During the year Ford also helped his friend and colleague Howard Hawks, who was having problems with his current film Red River (which starred John Wayne) and Ford reportedly contributed numerous editing suggestions, including the use of a narrator. Fort Apache was followed by another Western, 3 Godfathers, a remake of a 1916 silent film starring Harry Carey (to whom Ford’s version was dedicated), which Ford had himself already remade in 1919 as Marked Men, also with Carey and thought lost. It starred John Wayne, Pedro Armendáriz and Harry “Dobe” Carey Jr (in one of his first major roles) as three outlaws who rescue a baby after his mother (Mildred Natwick) dies in childbirth, with Ward Bond as the sheriff pursuing them.

In 1949 Ford briefly returned to Fox to direct Pinky. He prepared the project but worked only one day before falling ill, reportedly with shingles, and Elia Kazan replaced him (although Ford biographer Tag Gallagher thinks that Ford’s illness may have been a pretext for leaving the film, which Ford disliked).

His only completed film of that year was the second installment of his Cavalry Trilogy, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), starring John Wayne and Joanne Dru, with Victor McLaglen, John Agar, Ben Johnson, Mildred Natwick and Harry Carey Jr. Again filmed on location in Monument Valley, it was widely acclaimed for its stunning Technicolor cinematography (including the famous cavalry scene filmed in front of an approaching storm); it won Winton Hoch the 1950 Academy Award for Best Color Cinematography and did big business on its first release. John Wayne, then 41, also won wide praise for his role as the 60-year-old Captain Nathan Brittles.

Ford’s first film of 1950 was the offbeat military comedy When Willie Comes Marching Home, starring Dan Dailey and Corinne Calvet, with William Demarest, from Preston Sturges ‘stock company’, and early (uncredited) screen appearances by Alan Hale, Jr. and Vera Miles. It was followed by Wagon Master, starring Ben Johnson and Harry Carey Jr, which is particularly noteworthy as the only Ford film since 1930 that he scripted himself. It was subsequently adapted into the long-running TV series Wagon Train (with Ward Bond reprising the title role until his sudden death in 1960). Although it did far smaller business than most of his other films in this period, Ford cited Wagon Master as his personal favorite out of all his films, telling Peter Bogdanovich that it “came closest to what I had hoped to achieve”.

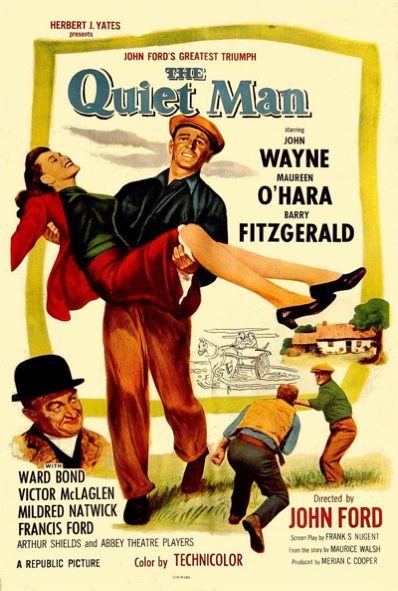

Rio Grande (1950), the third part of the ‘Cavalry Trilogy’, co-starred John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara, with Wayne’s son Patrick Wayne making his screen debut (he appeared in several subsequent Ford pictures including The Searchers). It was made at the insistence of Republic Pictures, which demanded a profitable Western as the condition of backing Ford’s next project, The Quiet Man. A testament to Ford’s legendary efficiency, Rio Grande was shot in just 32 days, with only 352 takes from 335 camera setups, and it was a solid success, grossing $2.25 million in its first year.

Republic’s anxiety was erased by the resounding success of The Quiet Man (1952), a pet project which Ford had wanted to make since the 1930s. It became his biggest grossing picture to date, taking nearly $4 million in the US alone in its first year and ranking in the top 10 box office films of its year. It was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won Ford his fourth Oscar for Best Director. It was followed by What Price Glory? (1952), a World War I drama, the first of two films Ford made with James Cagney (Mister Roberts was the other) which also did good business at the box office.

The Sun Shines Bright (1953), Ford’s first entry in the Cannes Film Festival, was a western comedy-drama with Charles Winninger reviving the Judge Priest role made famous by Will Rogers in the 1930s. Ford later referred to it as one of his favorites, but it was received poorly, and was drastically edited (from 90 to 65 minutes) by the studio soon after its release, with some excised scenes now presumed lost.

Ford’s next film was the romance-adventure Mogambo (1953), a loose remake of the celebrated 1932 film Red Dust. Filmed on location in Africa, it was photographed by British cinematographer Freddie Young and starred Ford’s old friend Clark Gable, with Ava Gardner, Grace Kelly (who replaced an ailing Gene Tierney) and Donald Sinden. Although the production was difficult (made more so by the irritating presence of Gardner’s then husband Frank Sinatra), Mogambo became one of the biggest commercial hits of Ford’s career, with the highest domestic first-year gross of any of his films ($5.2 million); it also revitalized Gable’s waning career and earned Best Actress and Best Supporting Actress Oscar nominations for Gardner and Kelly.

In 1955, Ford made the lesser-known West Point drama The Long Gray Line for Columbia Pictures, the first of two films of his to feature Tyrone Power, who had originally been slated to star as the adult Huw in How Green Was My Valley in 1941. Later in 1955 Ford was hired by Warner Brothers to direct the Naval comedy Mister Roberts, starring Henry Fonda, Jack Lemmon, William Powell, and James Cagney, but there was conflict between Ford and Fonda, who had been playing the lead role on Broadway for seven years and had misgivings about Ford’s direction. During a three-way meeting with producer Leland Hayward to try and iron out the problems, Ford became enraged and punched Fonda in the jaw, knocking him across the room, which threatened to cause a lasting rift between them. After the incident Ford became increasingly morose, drinking heavily and eventually retreating to his yacht, the Araner, and refusing to eat or see anyone. Production was shut down for five days while Ford sobered up, but soon afterward suffered a ruptured gallbladder, necessitating emergency surgery, and he was replaced by Mervyn LeRoy.

Ford also took his first steps into television in 1955, directing two half-hour dramas for network TV. In the summer of 1955 he made Rookie of the Year (Hal Roach Studios) for the TV series Studio Directors Playhouse; scripted by Frank S. Nugent, it featured Ford regulars John and Pat Wayne, Vera Miles and Ward Bond, with Ford himself appearing in the introduction. In November he made The Bamboo Cross (1955) for the Fireside Theater series; it starred Jane Wyman with an Asian-American cast and Stock Company veterans Frank Baker and Pat O’Malley in smaller roles.

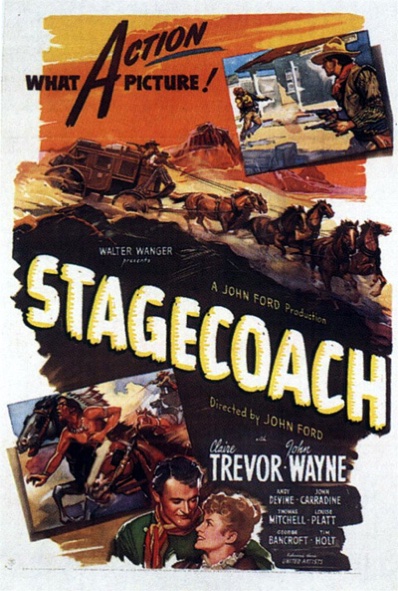

Ford returned to the big screen with The Searchers (Warner Bros, 1956), the only Western he made between 1950 and 1959, which is now widely regarded as not only one of his best films, but also by many as the greatest western ever made, and one of the best performances of John Wayne’s career. Shot on location in Monument Valley, it tells of the embittered Civil War veteran Ethan Edwards who spends years tracking down his niece, kidnapped by Comanches as a young girl. The supporting cast included Jeffrey Hunter, Ward Bond, Vera Miles and rising star Natalie Wood. It was Hunter’s first film for Ford. It was very successful upon its first release and became one of the top 20 films of the year, grossing $4.45 million, although it received no Academy Award nominations. However, its reputation has grown greatly over time — it was named the Greatest Western of all time by the American Film Institute in 2008 and placed 12th on the Institute’s 2007 list of the Top 100 greatest movies of all time. The Searchers has exerted a wide influence on film and popular culture — it has inspired (and been directly quoted by) many filmmakers, including David Lean and George Lucas, Wayne’s character’s catchphrase “That’ll be the day” inspired Buddy Holly to pen his famous hit song of the same name, and the British pop group The Searchers also took their name from the film.

The Searchers was accompanied by one of the first “making of” documentaries, a four-part promotional program created for the “Behind the Camera” segment of the weekly Warner Bros. Presents TV show, (the studio’s first foray into TV) which aired on ABC in 1955–56. Presented by Gig Young, the four segments included interviews with Jeffrey Hunter and Natalie Wood and behind-the-scenes footage shot during the making of the film.

The Wings of Eagles (1957) was a fictionalized biography of Ford’s old friend, aviator-turned-scriptwriter Frank “Spig” Wead, who had scripted several of Ford’s early sound films. It starred John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara, with Ward Bond as John Dodge (a character based on Ford himself). It was followed by one of Ford’s least known films, The Growler Story, a 29-minute dramatized documentary about the USS Growler. Made for the US Navy and filmed by the Pacific Fleet Command Combat Camera Group, it featured Ward Bond and Ken Curtis alongside real Navy personnel and their families.

Ford’s next two films stand somewhat apart from the rest of his films in terms of production, and he took no salary for either job. The Rising of the Moon (1957) was a three-part ‘omnibus’ movie shot on location in Ireland and based on Irish short stories. It was made by Four Province Productions, a company established by Irish tycoon Lord Killanin, who had recently become Chair of the International Olympic Committee, and to whom Ford was distantly related. Killanin was also the actual (but uncredited) producer of The Quiet Man. The film did not recoup its costs, and it stirred up controversy in Ireland.

Both of Ford’s 1958 films were made for Columbia Pictures and were significant departures from the director’s norm. Gideon’s Day (Gideon of Scotland Yard in the US) was adapted from a John Creasey novel and is Ford’s only police genre film, and one of the few Ford films set in the present day of the 1950s. It was shot in England with a British cast headed by Jack Hawkins, whom Ford uncharacteristically lauded as “the finest dramatic actor with whom I have worked”. It was poorly promoted by Columbia, and it too failed to make a profit.

The Last Hurrah, (1958), again set in present-day of the 1950s, starred Spencer Tracy, who had made his first film appearance in Ford’s Up The River in 1930. Tracy plays an aging politician fighting his last campaign, with Jeffrey Hunter as his nephew. Katharine Hepburn is said to have facilitated a rapprochement between the two men, ending a long-running feud, and she convinced Tracy to take the lead role, which had originally been offered to Orson Welles (but was turned down by Welles’ agent without his knowledge, and much to his chagrin). It did considerably better business than either of Ford’s two preceding films, although cast member Anna Lee said that Ford was “disappointed with the picture” and that Columbia had not permitted him to supervise the editing.

Korea: Battleground for Liberty (1959), Ford’s second documentary on the Korean War, was made for the US Department of Defense as an orientation film for US soldiers stationed there, and was soon followed by The Horse Soldiers (1959), a Civil War story starring John Wayne and William Holden. Although Ford expressed unhappiness with the project, it was a commercial success, ranking in the year’s Top 20 box-office hits, and earning Ford his highest-ever fee — $375,000, plus 10% of the gross.

In his last years Ford fought declining health, largely as a result of life-long heavy drinking and smoking, exacerbated by wounds he’d suffered in the Battle of Midway. His vision in particular deteriorated rapidly and at one point he briefly lost his sight; his prodigious memory also began to falter, making it necessary to rely more and more on assistants. His work was also restricted by the new regime in Hollywood, and he found it hard to get his projects made. By the 1960s he had been pigeonholed as a Western director and complained that he now found it almost impossible to get backing for projects in other genres.

Sergeant Rutledge (1960) was Ford’s last cavalry film. Set in the 1880s, it tells the story of an African-American cavalryman (Woody Strode) wrongfully accused of raping and murdering a white girl. It was erroneously marketed as a suspense film by Warners and was not a commercial success. During 1960, Ford made his third TV production, The Colter Craven Story, a one-hour episode of the network TV show Wagon Train, which included footage from Ford’s Wagon Master (on which the series was based). He also visited the set of The Alamo, produced, directed by, and starring John Wayne, where his interference drove Wayne to send him out to film second-unit scenes which were never used (nor intended to be) in the film.

Two Rode Together (1961) co-starred James Stewart and Richard Widmark, with Shirley Jones and Stock Company regulars Andy Devine, Henry Brandon, Harry Carey Jr, Anna Lee, Woody Strode, Mae Marsh and Frank Baker, with an early screen appearance by Linda Cristal, who went on to star in the Western TV series The High Chaparral. It was a fair commercial success, grossing $1.6m in its first year.

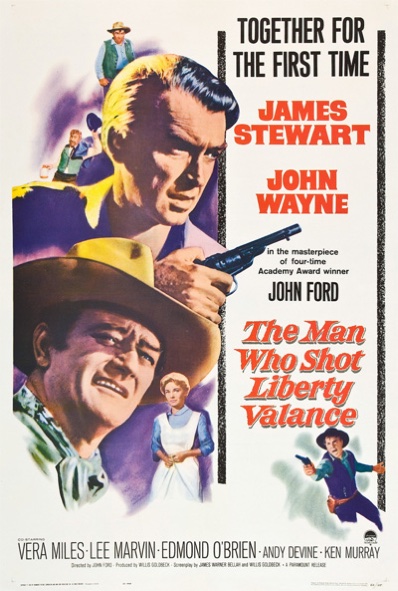

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) is frequently cited as the last great film of Ford’s career. It co-starred John Wayne and James Stewart, with Vera Miles, Edmond O’Brien, Andy Devine as the inept marshal Appleyard, Denver Pyle, John Carradine, and Lee Marvin in one of his first major roles as the brutal Valance, with Lee Van Cleef and Strother Martin as his henchmen. It is also notable as the film in which Wayne first used his trademark phrase “Pilgrim” (his nickname for James Stewart’s character). It was very successful, grossing over $3 million in its first year, although the lead casting stretched credibility — the characters played by Stewart (then 53) and Wayne (then 54) were meant to be in their early 20s, and Ford reportedly considered casting a younger actor in Stewart’s role but feared it would draw too much attention to Wayne’s age. Though it is often claimed that budget constraints necessitated shooting most of the film on sound stages on the Paramount lot, studio accounting records show that this was part of the film’s original artistic concept. According to Lee Marvin in a filmed interview, Ford had fought hard to shoot the film in black-and-white to accentuate his use of shadows. Still, it was one of Ford’s most expensive films at US$3.2 million.

After completing Liberty Valance, Ford was hired to direct the Civil War section of MGM’s epic How The West Was Won, the first non-documentary film to use the Cinerama wide-screen process. Ford’s segment featured George Peppard, with Andy Devine, Russ Tamblyn, Harry Morgan as Ulysses S. Grant, and John Wayne as William Tecumseh Sherman. Also in 1962, Ford directed his fourth and final TV production, Flashing Spikes, a baseball story made for the Alcoa Premiere series and starring James Stewart, Jack Warden, Patrick Wayne and Tige Andrews, with Harry Carey, Jr. and a large surprise appearance by John Wayne, billed in the credits as “Michael Morris”.

Donovan’s Reef (1963) was Ford’s last film with John Wayne. Filmed on location on the Hawaiian island of Kauai, it was a morality play disguised as an action-comedy, which subtly but sharply addressed issues of racial bigotry, corporate connivance, greed and American notions of societal superiority. The supporting cast included Lee Marvin, Elizabeth Allen, Jack Warden, Dorothy Lamour, and Cesar Romero. It was also Ford’s last commercial success, pulling in $3.3 million against a budget of $2.6 million.

Cheyenne Autumn (1964) was Ford’s epic farewell to the West, which he publicly called an elegy to the Native American. It was his last Western, his longest film, and the most expensive movie of his career ($4.2 million), but it failed to recoup its costs at the box office and lost about $1 million. The all-star cast was headed by Richard Widmark, with Carroll Baker, Karl Malden, Dolores del Río, Ricardo Montalbán, Gilbert Roland, Sal Mineo, James Stewart as Wyatt Earp, Arthur Kennedy as Doc Holliday, Edward G. Robinson, Patrick Wayne, Elizabeth Allen, Mike Mazurki and many of Ford’s faithful Stock Company, including John Carradine, Ken Curtis, Willis Bouchey, James Flavin, Danny Borzage, Harry Carey, Jr., Chuck Hayward, Ben Johnson, Mae Marsh and Denver Pyle. William Clothier was nominated for a Best Cinematography Oscar and Gilbert Roland was nominated for a Golden Globe award for Best Supporting Actor for his performance as Cheyenne elder Dull Knife.

In 1965 Ford began work on Young Cassidy, a biographical drama based on the life of Irish playwright Seán O’Casey, but he fell ill early in the production and was replaced by Jack Cardiff.

Ford’s last completed feature film was 7 Women (1966), a drama about missionary women in China (circa 1935) trying to protect themselves from the advances of a barbaric Mongolian warlord. Anne Bancroft took over the lead role from Patricia Neal, who suffered a near-fatal stroke two days into shooting. The supporting cast included Margaret Leighton, Flora Robson, Sue Lyon, Mildred Dunnock, Anna Lee, Eddie Albert, Mike Mazurki and Woody Strode, with music by Elmer Bernstein. It was a commercial flop, grossing only half of its $2.3 million budget. Unusual for Ford, it was shot in continuity for the sake of the performances, which necessitated the exposure of roughly four times as much film as he usually shot. Anna Lee recalled that Ford was “absolutely charming” to everyone and that the only major blow-up came when Flora Robson complained that the sign on her dressing room door did not include her title (“Dame”) and as a result Robson was “absolutely shredded” by Ford in front of cast and crew.

Ford’s next project, The Miracle of Merriford, was scrapped by MGM less than a week before shooting was set to start. His last completed work was Chesty: A Tribute to a Legend, a documentary on the most decorated U.S. Marine, General Lewis B. Puller, with narration by John Wayne, which was made in 1970 but not released until 1976, three years after Ford’s death.

Ford’s health declined rapidly in the early 1970s; he suffered a broken hip in 1970, which put him in a wheelchair. He had to move from his Bel Air home to a single-level house in Palm Desert, California, near Eisenhower Medical Center, where he was being treated for cancer. In October 1972, the Screen Directors Guild staged a tribute to Ford and in March 1973 the American Film Institute honored him with its first Lifetime Achievement Award, at a ceremony that was telecast nationwide, with President Richard Nixon promoting Ford to full Admiral and presenting him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Ford died on August 31, 1973 at Palm Desert. His funeral was held on September 5th at Hollywood’s Church of the Blessed Sacrament. He was interred in Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City, California.

Ford was renowned for his intense personality and his many idiosyncrasies and eccentricities. Beginning in the early Thirties, he always wore dark glasses and a patch over his left eye, which was only partly to protect his poor eyesight. He was an habitual pipe-smoker and while shooting he would chew on linen handkerchiefs — each morning his wife gave him a dozen fresh handkerchiefs, but by the end of a day’s filming the corners of all of them had been chewed to shreds. He always had music played on the set and would routinely break for tea (Earl Grey) at mid-afternoon every day during filming. He discouraged chatter and disliked bad language on set; its use, especially in front of a woman, typically resulted in the offender being ejected from the production. He rarely drank during the making of a film, but after a production wrapped he was given to locking himself in his study, wrapped only in a sheet, and going on solitary drinking binges for days at a time, followed by routine bouts of contrition and vows never to drink again. He was extremely sensitive to criticism and always particularly angered by any comparison between his work and that of his older brother Francis. He was rarely seen at premieres or award ceremonies, although he proudly displayed his Oscars and other awards on the mantle in his home.

He was famously untidy, and his study was always littered with books, papers and clothes. He bought a brand new Rolls-Royce in the 1930s, but never rode in it because his wife Mary would not let him smoke in it. His own car, a battered Ford roadster, was so dilapidated and messy that he was once late for a studio meeting because the guard at the studio gate did not believe that the real John Ford would drive such a car, and refused to let him in. He was also notorious for his antipathy towards studio executives: on one early film for Fox he is said to have ordered a guard to keep studio boss Darryl F. Zanuck off the set, and on another occasion he brought an executive in front of the crew, stood him in profile and announced, “This is an associate producer — take a good look because you won’t be seeing him on this picture again”.

His pride and joy was his yacht, christened “Araner”, which he bought in 1934 and on which he lavished hundreds of thousands of dollars in repairs and improvements over the years; it became his preferred retreat between films and a meeting place for his circle of close friends, including John Wayne and Ward Bond.

Ford was brilliant, erudite, sensitive and sentimental, but to protect himself in the cutthroat environment of Hollywood he cultivated the image of a “tough, two-fisted, hard-drinking Irish sonofabitch”. One famous event, witnessed by Ford’s friend actor Frank Baker, is a striking illustration of the tension between the public persona and the private man. During the Depression, Ford — who by then was very wealthy — was approached outside his office by a former actor who was destitute and needed $200 for an operation for his wife. As the man related his misfortunes, Ford appeared to become enraged and then, to the horror of witnesses, he launched himself at the man, knocked him to the floor and shouted “How dare you come here like this? Who do think you are to talk to me this way?” before storming out of the room. However, as the shaken old man left the building, Frank Baker saw Ford’s business manager Fred Totman meet him at the door, where he handed the man a cheque for $1,000 and instructed Ford’s chauffeur to drive him home. There, an ambulance was waiting to take the man’s wife to the hospital where a specialist, flown in from San Francisco at Ford’s expense, performed the operation. Some time later, Ford bought a house for the couple and pensioned them for life.

Ford had many distinctive stylistic trademarks. Many thematic threads and visual/aural motifs recur through his work. According to journalist Ephraim Katz:

Of all American directors, Ford probably had the clearest personal vision and the most consistent visual style. His ideas and his characters are, like many things branded “American”, deceptively simple. His heroes… may appear simply to be loners, outsiders to established society, who generally speak through action rather than words. But their conflict with society embodies larger themes in the American experience.

Ford’s films, particularly the Westerns, express a deep aesthetic sensibility for the American past and the spirit of the frontier… his compositions have a classic strength in which masses of people and their natural surroundings are beautifully juxtaposed, often in breathtaking long shots. The movement of men and horses in his Westerns has rarely been surpassed for regal serenity and evocative power. The musical score, often variations on folk themes, plays a more important part than dialogue in many Ford films.

Ford also championed the value and force of the group, as evidenced in his many military dramas… (he) expressed a similar sentiment for camaraderie through his repeated use of certain actors in the lead and supporting roles… he also felt an allegiance to places…

In contrast to his contemporary Alfred Hitchcock, Ford never used storyboards, composing his pictures entirely in his head, without any written or graphic outline of his shots ahead of time. Script development could be intense but, once approved, his screenplays were seldom rewritten; he was also one of the first filmmakers to encourage his writers and actors to prepare full back stories for their characters. He hated long expository scenes and was famous for tearing pages out of a script to cut dialogue. During the making of Mogambo, when challenged by the film’s producer Sam Zimbalist about falling three days behind schedule, Ford’s answer was to tear three pages out of the script and declare “We’re on schedule” — and true to his word he never filmed those pages. While making Drums Along the Mohawk, Ford neatly parried the challenge of shooting an expensive battle scene — he had Henry Fonda improvise a monologue while firing questions from behind the camera about the course of the battle (a subject on which Fonda was well-versed) and then simply editing out the questions.

He was sparing in his use of camera movements and close-ups, favoring static medium or long shots instead, with his players juxtaposed against dramatic vistas or interiors lit in an Expressionistic style, although he often used panning shots and sometimes used a dramatic dolly in (e.g. John Wayne’s first appearance in Stagecoach). Ford is justly celebrated for his exciting tracking shots, such as the Apache chase sequence in Stagecoach or the attack on the Comanche camp in The Searchers.

Recurring visual motifs include trains and wagons — many Ford films begin and end with linking vehicles such as a train or wagon arriving and leaving — doorways, roads, flowers, rivers, gatherings (parades, dances, meetings, bar scenes, etc.); he also utilized gestural motifs, such as the throwing of objects and the lighting of lamps, matches or cigarettes. If a doomed character was seen playing poker (such as Liberty Valance or the gunman Tom Tyler in Stagecoach), the last hand he plays is the “death hand” — two eights and two aces, one of them the ace of spades — so-called because Wild Bill Hickok is reputed to have held this hand when he was murdered. Many of his sound films include renditions or quotations of his favorite hymn, “Shall We Gather at the River?”, such as its parodic use to underscore the opening scenes of Stagecoach, when the prostitute Dallas is run out of town by local matrons. Character names also recur in many Ford films — the name Quincannon, for instance, appears in several films: The Lost Patrol, Rio Grande, She Wore A Yellow Ribbon and Fort Apache.

Ford was legendary for his discipline and efficiency on-set. He was notorious for his extreme toughness on actors, frequently mocking, yelling and bullying them; he was also infamous for his occasionally sadistic practical jokes. Any actor dumb enough to insist on star treatment was treated to the full force of his scorn and sarcasm. Ford once referred to John Wayne as a “big idiot” and even punched Henry Fonda. Henry Brandon (Chief Scar from The Searchers) once said of Ford that he was “the only man who could make John Wayne cry.” He belittled Victor McLaglen in similar fashion, on one occasion reportedly bellowing through the megaphone: “D’ya known, McLaglen, that Fox are paying you $1200 a week to do things that I could get any child off the street to do better?”. Ward Bond was reputedly one of the few actors impervious to Ford’s verbal assaults.

Sir Donald Sinden, a contract star when he starred in Mogambo, wasn’t the only person to suffer at the hands of Ford. He recalls:

“Ten White Hunters were seconded to our unit for our protection and to provide fresh meat. Among them was Marcus, Lord Wallscourt, a delightful man whom Ford treated abysmally — sometimes very sadistically. In Ford’s eyes the poor man could do nothing right and was continually being bawled out in front of the entire unit… None of us could understand the reason for this appalling treatment, which the dear kind man in no way deserved. He himself was quite at a loss. Several weeks later we discovered the cause from Ford’s brother-in-law: before emigrating to America, Ford’s grandfather had been a laborer on the estate in Ireland of the then Lord Wallscourt: Ford was now getting his own back at his descendant. Not a charming sight.”

“We now had to return to the MGM-British Studios in London to shoot all the interior scenes. Someone must have pointed out to Ford that he had been thoroughly foul to me during the entire location shoot and when I arrived for my first day’s work, I found that he had caused a large notice to be painted at the entrance to our sound stage in capital letters reading BE KIND TO DONALD WEEK. He was as good as his word — for precisely seven days. On the eighth day he ripped the sign down and returned to his normal bullying behavior.”

Ford typically gave his actors little explicit direction, although sometimes he would walk casually through a scene himself, and actors were expected to pay attention to every subtle action or mannerism; if they did not, Ford made them repeat the scene until they got it right, and he would often berate and belittle those who failed to achieve his desired performance. On The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Ford ran through a scene with Edmond O’Brien and ended by drooping his hand over a railing. O’Brien noticed this but deliberately ignored it, placing his hand on the railing instead; Ford would not explicitly correct him and he reportedly made O’Brien play the scene forty-two times before the actor relented and did it Ford’s way.

Despite his often difficult and demanding personality, many actors who worked with Ford acknowledged that he brought out the best in them. John Wayne remarked that “Nobody could handle actors and crew like Jack,” and Dobe Carey recalled that “He had a quality that made everyone almost kill themselves to please him. Upon arriving on the set, you would feel right away that something special was going to happen. You would feel spiritually awakened all of a sudden.” Carey credits Ford with the inspiration of Carey’s final film, Comanche Stallion (2005).

Ford’s favorite location for his Westerns was Monument Valley. Although not often appropriate geographically as a setting for his plots, the expressive visual impact of the area enabled Ford to define images of the American West with some of the most beautiful and powerful cinematography ever shot, in such films as Stagecoach, The Searchers, and Fort Apache. A notable example is the famous scene in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon in which the cavalry troop is photographed against an oncoming storm. Ford’s use of the territory for his Westerns has defined the images of the American West so powerfully that Orson Welles once said that other film-makers refused to shoot in the region out of fears of plagiarism.

Ford typically shot only the footage he needed and often filmed in sequence, minimizing the job of his film editors. His technique of cutting in the camera allowed him to retain creative control in a period where directors often had little say on the final editing of their films. Said Ford:

I don’t give ’em a lot of film to play with. In fact, Eastman used to complain that I exposed so little film. I do cut in the camera. Otherwise, if you give them a lot of film ‘the committee’ takes over. They start juggling scenes around and taking out this and putting in that. They can’t do it with my pictures. I cut in the camera and that’s it. There’s not a lot of film left on the floor when I’m finished.

John Ford’s directing credits include…

| Year | Movie |

|---|---|

| 1976 | Chesty: A Tribute to a Legend (Documentary) |

| 1966 | 7 Women |

| 1965 | Young Cassidy (uncredited) |

| 1964 | Cheyenne Autumn |

| 1963 | Donovan’s Reef |

| 1962 | How the West Was Won (segment “The Civil War”) |

| 1962 | Alcoa Premiere (TV Series — 1 episode) |

| 1962 | The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance |

| 1961 | Two Rode Together |

| 1960 | Wagon Train (TV Series — 1 episode) |

| 1960 | Sergeant Rutledge |

| 1959 | Korea (Documentary short) |

| 1959 | The Horse Soldiers |

| 1958 | The Last Hurrah |

| 1958 | Gideon of Scotland Yard |

| 1957 | The Rising of the Moon |

| 1957 | The Wings of Eagles |

| 1956 | The Searchers |

| 1955 | Screen Directors Playhouse (TV Series — 1 episode) |

| 1955 | Jane Wyman Presents The Fireside Theatre (TV Series — 1 episode) |

| 1955 | Mister Roberts |

| 1955 | The Long Gray Line |

| 1953 | Mogambo |

| 1953 | The Sun Shines Bright |

| 1952 | What Price Glory |

| 1952 | The Quiet Man |

| 1951 | This Is Korea! (Documentary) |

| 1950 | Rio Grande |

| 1950 | Wagon Master |

| 1950 | When Willie Comes Marching Home |

| 1949 | She Wore a Yellow Ribbon |

| 1949 | Pinky (uncredited) |

| 1949 | Fireside Theatre (TV Series) |

| 1948 | 3 Godfathers |

| 1948 | Fort Apache |

| 1947 | The Fugitive |

| 1946 | My Darling Clementine |

| 1945 | They Were Expendable |

| 1944 | Undercover (Documentary) (uncredited) |

| 1943 | December 7th: The Movie |

| 1943 | German Industrial Manpower (Documentary) |

| 1943 | How to Operate Behind Enemy Lines |

| 1943 | We Sail at Midnight (Documentary short) (uncredited) |

| 1943 | At the Front in North Africa with the U.S. Army (Documentary short) (uncredited) |

| 1942 | Torpedo Squadron (Documentary short) |

| 1942 | The Battle of Midway (Short documentary) |

| 1942 | Sex Hygiene (Short) (dramatic sequences) |

| 1941 | How Green Was My Valley |

| 1941 | Tobacco Road |

| 1940 | The Long Voyage Home |

| 1940 | The Grapes of Wrath |

| 1939 | Drums Along the Mohawk |

| 1939 | Young Mr. Lincoln |

| 1939 | Stagecoach |

| 1938 | Submarine Patrol |

| 1938 | Four Men and a Prayer |

| 1937 | The Hurricane |

| 1937 | Wee Willie Winkie |

| 1936 | The Plough and the Stars |

| 1936 | Mary of Scotland |

| 1936 | The Prisoner of Shark Island |

| 1935 | Steamboat Round the Bend |

| 1935 | The Informer |

| 1935 | The Whole Town’s Talking |

| 1934 | Judge Priest |

| 1934 | The World Moves On |

| 1934 | The Lost Patrol |

| 1933 | Doctor Bull |

| 1933 | Pilgrimage |

| 1932 | Flesh (uncredited) |

| 1932 | Air Mail |

| 1931 | Arrowsmith |

| 1931 | The Brat |

| 1931 | Seas Beneath |

| 1930 | Up the River |

| 1930 | Born Reckless |

| 1930 | Men Without Women |

| 1929 | Salute (uncredited) |

| 1929 | The Black Watch |

| 1929 | Strong Boy |

| 1928 | Riley the Cop (uncredited) |

| 1928 | Napoleon’s Barber (Short) |

| 1928 | Hangman’s House (uncredited) |

| 1928 | Four Sons |

| 1928 | Mother Machree (uncredited) |

| 1927 | Upstream |

| 1926 | The Blue Eagle (uncredited) |

| 1926 | 3 Bad Men |

| 1926 | The Shamrock Handicap |

| 1925 | The Fighting Heart |

| 1925 | Thank You |

| 1925 | Kentucky Pride |

| 1925 | Lightnin’ |

| 1924 | Hearts of Oak |

| 1924 | The Iron Horse (uncredited) |

| 1923 | Hoodman Blind |

| 1923 | North of Hudson Bay |

| 1923 | Cameo Kirby |

| 1923 | Three Jumps Ahead |

| 1923 | The Face on the Bar-Room Floor |

| 1922 | I The Village Blacksmith |

| 1922 | Silver Wings (as Jack Ford, prologue only) |

| 1922 | Little Miss Smiles |

| 1921 | Jackie |

| 1921 | Sure Fire |

| 1921 | Action |

| 1921 | Desperate Trails |

| 1921 | The Wallop |

| 1921 | The Freeze-Out |

| 1921 | The Big Punch |

| 1920 | Just Pals |

| 1920 | Hitchin’ Posts |

| 1920 | The Girl in Number 29 |

| 1920 | The Prince of Avenue A |

| 1919 | Marked Men |

| 1919 | A Gun Fightin’ Gentleman |

| 1919 | Rider of the Law |

| 1919 | Ace of the Saddle |

| 1919 | The Outcasts of Poker Flat |

| 1919 | The Last Outlaw (Short) |

| 1919 | Riders of Vengeance |

| 1919 | By Indian Post (Short) |

| 1919 | The Gun Packer (Short) |

| 1919 | Gun Law (Short) |

| 1919 | Bare Fists |

| 1919 | Rustlers (Short) |

| 1919 | A Fight for Love |

| 1919 | The Fighting Brothers (Short) |

| 1919 | Roped |

| 1918 | Three Mounted Men |

| 1918 | The Craving |

| 1918 | A Woman’s Fool |

| 1918 | Hell Bent |

| 1918 | The Scarlet Drop |

| 1918 | Thieves’ Gold |

| 1918 | Wild Women |

| 1918 | The Phantom Riders |

| 1917 | Bucking Broadway |

| 1917 | A Marked Man |

| 1917 | The Secret Man |

| 1917 | Straight Shooting |

| 1917 | Cheyenne’s Pal (Short) |

| 1917 | The Soul Herder (Short) |

| 1917 | The Scrapper (Short) |

| 1917 | The Trail of Hate (Short) |

| 1917 | The Tornado (Short) |

Memorable Quotes by John Ford

“I love making pictures but I don’t like talking about them.”

“Anybody can direct a picture once they know the fundamentals. Directing is not a mystery, it’s not an art. The main thing about directing is: photograph the people’s eyes.”

“It’s no use talking to me about art, I make pictures to pay the rent.”

“I didn’t show up at the ceremony to collect any of my first three Oscars. Once I went fishing, another time there was a war on, and on another occasion, I remember, I was suddenly taken drunk.”

“For a director there are commercial rules that it is necessary to obey. In our profession, an artistic failure is nothing; a commercial failure is a sentence. The secret is to make films that please the public and also allow the director to reveal his personality.”

“[on John Wayne] Duke is the best actor in Hollywood.”

Things You May Not Know About John Ford

John Wayne gave the eulogy at his funeral.

A young would-be director once came to him for advice, and Ford pointed out two landscape photographs in his office. One had the horizon at the top of the picture, and the other had it at the bottom of the picture. Ford said “when you know why the horizon goes at the top of the frame or the bottom of a frame, then you’re a director,” and threw the kid out of his office. The would-be director was Steven Spielberg.

Prior to making The Searchers (1956), Ford entered the hospital for the removal of cataracts. While recuperating after the surgery, he became impatient with the bandages covering his eyes and tore them off earlier than his doctors told him to. The result of that rash action was that Ford suffered a total loss of sight in one eye, which is how he came to wear his famous eyepatch.

Embarrassed Jean-Luc Godard, then a young journalist for “Les Cahiers du Cinema”, during an interview. When Godard asked the famous question, “What brought you to Hollywood?” Ford replied, “A train”.

His apparently madcap affair with Katharine Hepburn, when both were married, inspired his friend Dudley Nichols to write the script for Bringing Up Baby (1938). When (after Hepburn broke off her relationship with Ford) she began her lifelong affair with Spencer Tracy, Ford was allegedly incensed and, after the two had had a fruitful collaboration early on in their careers, he neither spoke with nor worked with Tracy for about 20 years.

John Wayne usually called him by the nickname “Coach” or “Pappy” in private, but several times publicly, including during Wayne’s acceptance speech for the 1970 Oscar for Best Actor, Wayne called him “Admiral John Ford”, in reference to Ford’s rank at retirement from the U.S. Naval Reserves.