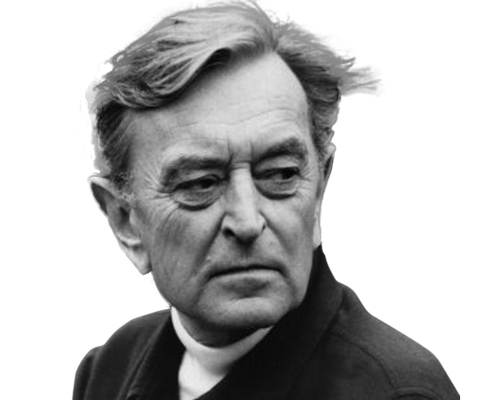

David Lean

Best known for his sprawling cinematic epics, particularly The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and Doctor Zhivago (1965). He is also noted for the Dickens adaptations of Great Expectations (1946) and Oliver Twist (1948), as well as the romantic drama Brief Encounter (1945).

From 1956 to his death in 1991, David Lean completed five films. Three of them are in the American Film Institute’s Top 40 films of all time: “Lawrence of Arabia“, “Dr. Zhivago“, and “The Bridge on the River Kwai“.

Lean was as meticulous as Hitchcock in preparing every scene and every line of dialogue of his films. Though sometimes many years passed between films, Lean was working all the time, preparing. Though he was notoriously tough on his cast and crew — supposedly the inspiration for Peter O’Toole’s director in “The Stunt Man” — many of them came back for multiple Lean years.

Like Hitchcock, too, Lean had an extremely strict upbringing. Born into a Quaker family in England in 1908, he had to sneak into the movies until he was an adult. He worked as a clapper boy, eventually becoming an editor. (He edited “A Passage to India”, his last film.) His first films were adaptations of Noel Coward plays, including “Blithe Spirit”, ironically as confined a film as you can find. David’s next projects were exemplary versions of Dickens classics “Oliver Twist” and “Great Expectations”.

Unlike many contemporary epic directors, David Lean matched the breathtaking scope of his scenes with a mastery of complex central characters. “Doctor Zhivago” features a host of them. Alec Guinness’s Col. Nicholson in “Kwai” and Peter O’Toole’s T.E. Lawrence are two of the most conflicted, puzzled and enigmatic heroes that have ever strutted the wide screen.

These characters and their fascinating stories are the true source of the timelessness of Lean’s films, though we certainly appreciate the vastness of his canvas. Interestingly, the one thing the four epics have in common is an anti-imperialist view (though the targeted empire is certainly not always British). The Big Three also have a decidedly anti-war theme in common, in spite of “Kwai” and “Lawrence” exulting in more than their share of heroes.

Lean went through as many wives as he did epics: six. Though he kept mum about his private life, he paid the price for his “roaming eye”, never staying married for long. (One has to wonder about the sanity of wives four, five and six.)

Though he exuded the autocratic style and self-confidence of a big-picture dude, his vulnerability to criticism kept him in hiding for fourteen years after the poor critical reception to “Ryan’s Daughter“. A pity! Somehow, he forgot that his three epics won a combined total of 21 Academy Awards.

— Nate Lee

Great Scenes

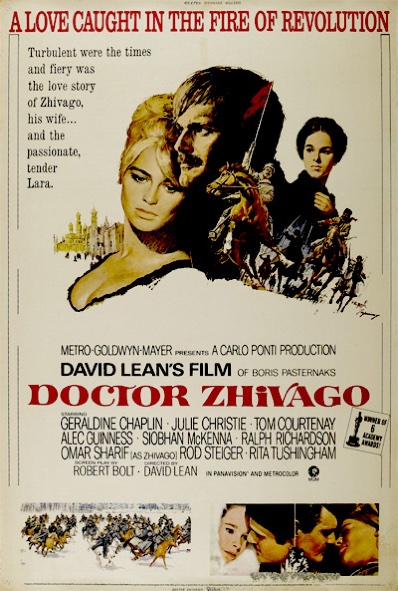

Doctor Zhivago

- Notice the tragic parallel bookend scenes of Zhivago on the streetcar: early in the film, Omar Sharif runs after the streetcar, hops on, sits in front of Julie Christie, but keeps (maddeningly) turning away and never sees her. At the end of the film, he is sitting on the streetcar and sees Christie out the window. He squeezes out of the car and runs after her, only to have a heart attack before catching up to her. Watch both scenes back-to-back to appreciate the essence of their personal tragedy

- The whole “ice palace” sequence is unique in its visual splendor, but especially note the howling “steppenwolves” standing in for the imminent Reds

- The special features on the DVD are fascinating

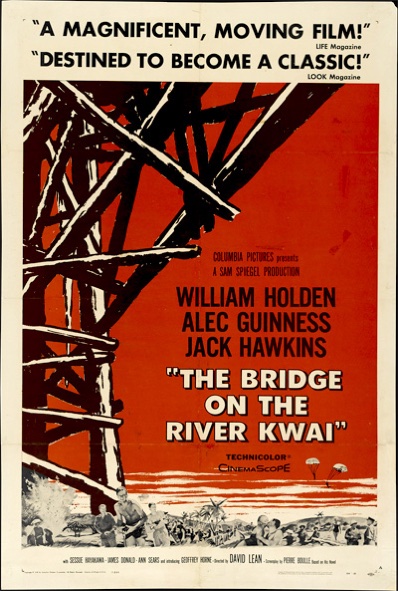

Bridge on the River Kwai

- The whistling “Captain Bogey” march over the finished bridge isn’t as cool as the same march into the camp, but everything after that and leading up to the blowing up of the bridge is one of the best scenes in action cinema yet is completely character driven.

- The final line of the film, “Madness! Madness!” could be construed as unnecessary, but it forces one into accepting this war film as an anti-war film

- Two of the best scenes are two of the smallest: during a meal of Scotch and corned beef, Alec Guinness’s Col. Nicholson gains the upper hand over the prison-camp commandant, Col Saito; and, again, in his office, Nicholson’s men throw out the Japanese bridge plans and replace them with their own

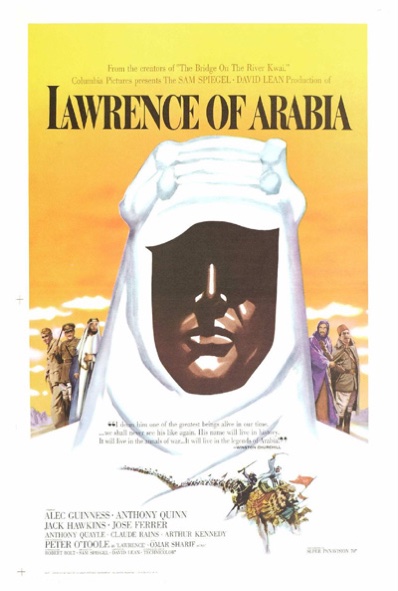

Lawrence of Arabia

- When Lawrence comes into the officers’ mess, a hero, dressed in Arab garb and toting a young boy, you can’t help but laugh and cheer at the same time

- The charge into Aqaba and the charge at the exploded train are so grand, you are hard-pressed to remember that this is all pre-ILM; there are no computer-generated horses here. This is the real thing

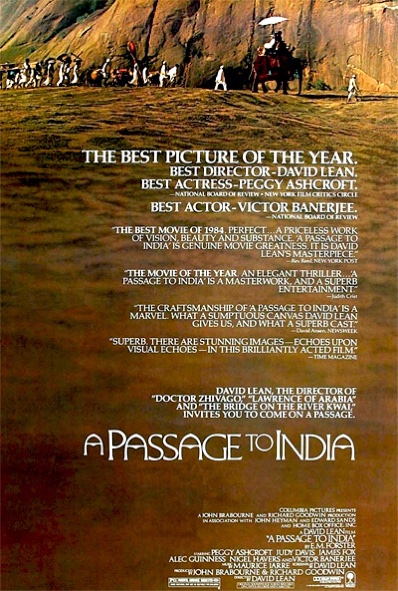

A Passage to India

- Lean’s brilliance as an editor, too, is evident throughout but none more so than the surprising trial scene

- The British ladies (Peggy Ashcroft and Judy Davis) go from spectators to quasi-participants and spectacle as they board the colorful elephant on their way to the caves

Epics

- Bridge on the River Kwai

- Lawrence of Arabia

- Doctor Zhivago

- Passage to India

Other Great Films

- Summertime

- Oliver Twist (1948)

- Hobson’s Choice

- Blithe Spirit